The Son of Heaven at Central High School

In 1989, a groundbreaking exhibit of imperial Chinese artifacts came to Columbus, Ohio. It was supposed to tour the nation. Then Tiananmen Square happened.

The 80-mile drive to Columbus was a reliable two hours throughout my childhood. Half an hour and you came to Logan; hit Lancaster and you were halfway there. Before I could read, I spent my time in the backseat gazing out the window. The first town on Route 33 was Nelsonville, 15 minutes out. Today, it’s home to a shockingly awesome annual music festival and other arts outlets, but for most of my life, Nelsonville was something to pass through, a once-thriving coal town starved of jobs and a tax base.

As you crawled up Canal Street, off to the left, you could see a car wash, a Domino’s, a vacancy, another. Farther back stood a smokestack, which I mistook for a bell tower, or maybe a pagoda. I remember it looming against grim wintry cloud cover. I was five or six, and 15 minutes in the car probably felt indistinguishable from two hours. “Is that Son of Heaven?” I asked my parents, who chuckled. No emperor of any sort would set foot in Nelsonville, Ohio.

But we had gone to see Son of Heaven after one of these car rides. Two hundred and twenty-five artifacts from 26 centuries of imperial China lived in Columbus for eight months in 1989. Most had only been unearthed in the last few decades and had never been seen outside of China. The novelty was undeniable on a grander scale too: the United States had only reinstated formal diplomatic relations with China 10 years earlier; the famous Terracotta Army of the first Qin emperor was unearthed in Xi’an just 15 years prior.

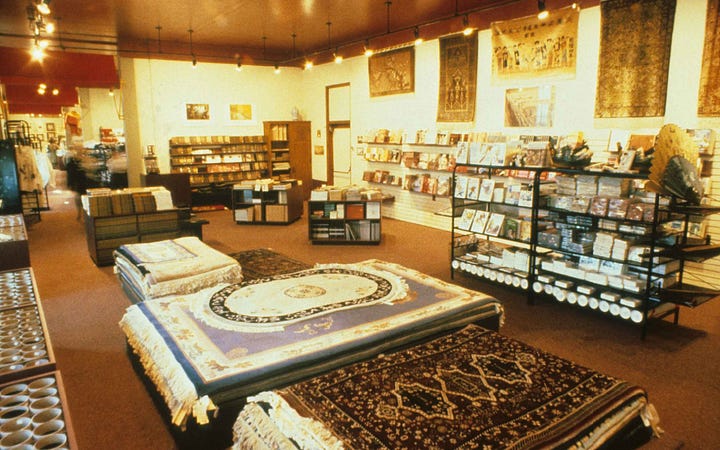

Longtime Columbusites, Ohioans and aficionados of the museum blockbuster may recall “Son of Heaven: Imperial Arts of China” as a boondoggle, an overhyped mess, a money sink that didn’t pay off — and as a horizon-expanding encounter with astonishing cultural richness. My dad, a lifelong academic, called it the first time he saw and understood historical Chinese arts that were not heavily stylized or mediated but rather naturalistic, even realistic. I’m not sure if my own memories are of the exhibit itself or of its stunning full-color catalog, which I adored as a kid. Some of the picture books I loved most growing up probably came from its gift shop.

![A commemorative coffee mug cost $5.95. [Fred Squillante/Dispatch] A commemorative coffee mug cost $5.95. [Fred Squillante/Dispatch]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!wFUB!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa5dd0758-c373-4428-8b0c-e6f55af16da0_660x415.jpeg)

This show landing in the “cow town” Columbus of 1989 has been an object of fascination to me for years. Columbus was the exhibition’s second stop, after opening in Seattle the previous year — and its finale. “Son of Heaven” was supposed to tour the U.S. as a long-term spectacle, but by April 1990, the corporation set up to manage it was liquidating its assets, the artifacts dispersed back to Beijing.

I’ve been trying to learn why. That “Son of Heaven” opened in Columbus just before the Tiananmen Square Massacre may play a role; the finances of the entire endeavor also reveal some strange but powerful competing interests. Not a lot of postmortems are available online, if they were published at the time, and the reporting required 35 years after the fact is time- and resource-intensive.

But this is an invitation to any commissioning editors who would like to fund a deeper dive — do please reach out if you’d like to work together. I think “Son of Heaven” offers a fascinating window into prestige jockeying among self-conscious midsized cities, cultural artifacts as tools of soft diplomacy, diaspora perspectives in isolated communities and how Ohioans of all stripes experienced a visit from the outside world before it became so widely available to us.

Every conceivable kind of treasure

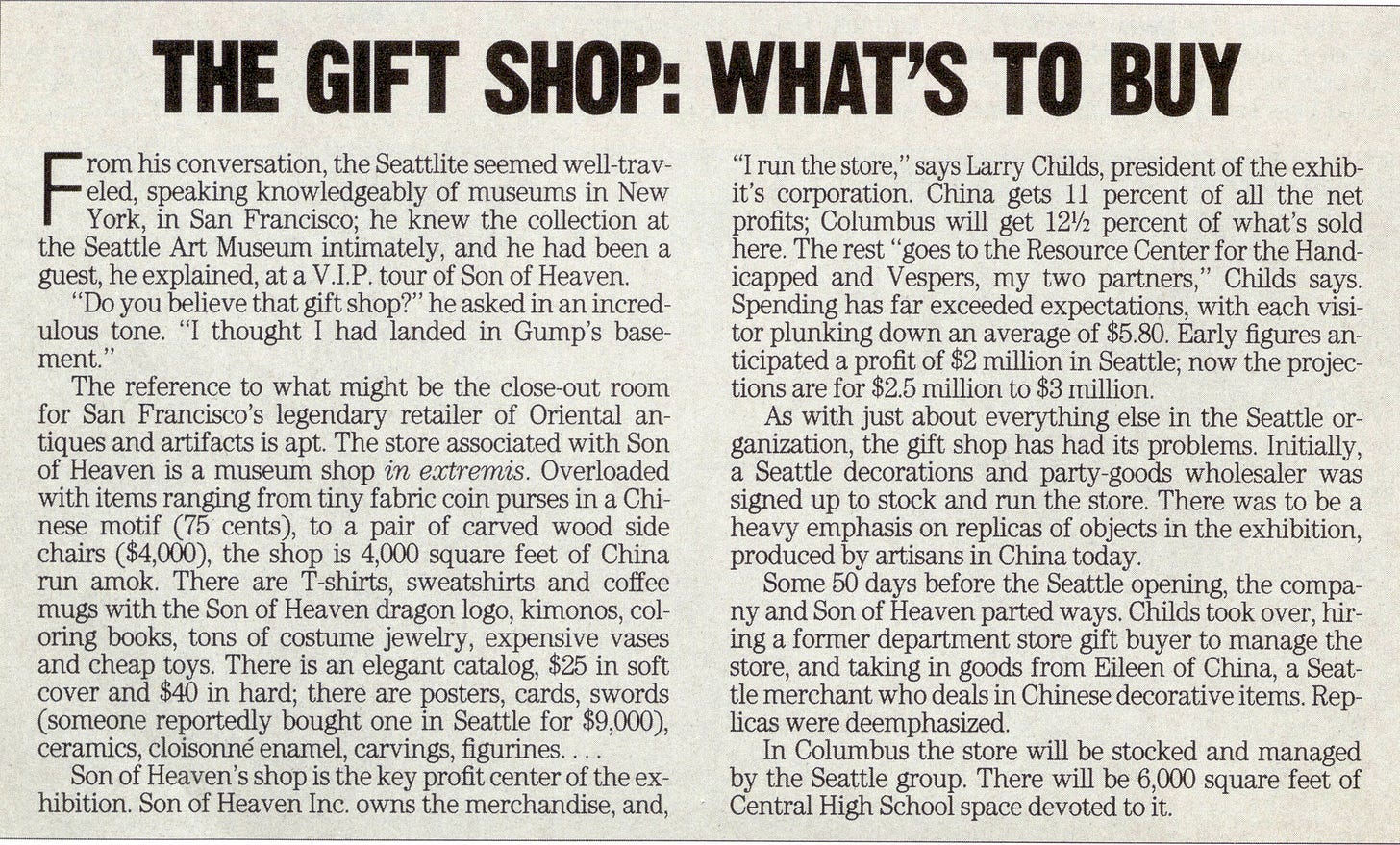

The average ticket for “Son of Heaven” in March 1989, the month it opened in Columbus, cost $7.50; according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ inflation calculator, that’s nearly $20 today. More than a week before opening, ticket presales stood around 85,000. In the preceding months, “Columbus schoolchildren were learning ancient Chinese history to prepare for field trips, and Ohio State University added a series of ‘Son of Heaven’ lectures to its continuing education curriculum,” wrote Meg Reynolds for the Associated Press. “A downtown department store since last fall has devoted a section of its first floor to ‘Son of Heaven’ sweatshirts, T-shirts and mugs.”

Ohio was primed and ready to show up, and what a spectacle awaited them. The old Central High School had been specially converted (in only six months) into a series of imperial spaces: Altar, Outer Court, Temple, Inner Court, Tomb. (Of the last, architect John Schooley deadpanned, “For a boys old locker room, it's not bad.”) Many of the artifacts will be familiar to fans of palace dramas: exquisite embroidered silk emblems denoting the rank and role of Qing ministers, elaborate bronze braziers shaped as guardian deities, fragile ink-wash paintings, blue-and-white Tang and Ming vases, carved inkstones, miraculous gold headdresses, the Dragon Throne.

Other pieces are, even in photographs, more startling and mysterious. The small ceramic servants buried alongside their master. The sheer detail and individuality of each terracotta warrior and his horse. Twenty-six bronze temple bells from the sixth century BCE, still playable. The full-body jade suit, 200 panels joined with gold thread, for a princess who believed, more than 2,200 years ago, that it would keep her body perfectly preserved. All of these, curator Robert Thorp notes in the short video above, presented “so you can get very, very close to them … in a way they really cannot be seen in China.”

People did get close, and they traveled from all over the country to see these treasures — 600,000 in Columbus, half a million in Seattle. One visitor was 104-year-old Fun Ai Chao Lum: “Escorted by Liu Shishu, chief curator, the elderly woman listened intently as the curator’s Mandarin was translated into her native Cantonese. ‘She remembers the last three emperors very well,’ the woman’s son said. ‘Anything before that is a little fuzzy.’”

As an exhibit, “Son of Heaven” stood tall on its merits. It proved so popular in Columbus that its run was extended two months. Local officials were eager to prove they were ready for AmeriFlora ‘92 and the cultural big leagues in general. This was intended as a benchmark event, comparable to touring ‘80s blockbusters on El Greco and Tutankhamun. In November 1989, from the outside, everyone seemed to be winning. After “Son of Heaven” closed, Janet Steinberg proclaimed in the Cincinnati Enquirer, “Ohio’s capital city is becoming so vibrant and sophisticated that it recently pulled off the coup of the decade.”

The exhibition was supposed to move on to another city after dazzling Columbus — as far as I can tell, two of the three final candidates were Denver and Orlando, Florida. Instead, within six months, it all went belly up. The gift shop’s wares were auctioned off at a loss. Rather than seeing profits, both previous hosts were left, if not in the dust, then definitively in the red.

“There were holes in their cheese”

When “Son of Heaven” closed in Seattle, early reports indicated the show had earned $600,000 in profits, more than $1.5 million today. A year later, helicopter tours pioneer and Son of Heaven Inc. chairman Elling Halvorson was forced to announce that in fact, the show had tanked in Seattle, to the tune of $2 million in debt (nearly $5.2 million today).

Columbus had invested $2.3 million alone in renovating the old Central High School, which did at least pay off in the long term — half that budget was for HVAC and electrical upgrades, and visitors to the city today will recognize the building as “new” COSI, opened in 1999. But “Son of Heaven” incurred a $1.67 million deficit in Columbus, which was shouldered by the city and the state of Ohio.

The exhibition’s creaky finances were not secret before its abortive U.S. tour. A long Columbus Monthly article detailed the strong competing interests driving up costs behind the scenes in December 1988. The pressure to be fast, good and cheap laid the groundwork for many of the problems which hobbled “Son of Heaven” down the line. One of the show’s earliest backers spent several years pitching it to museums; all of them declined, on the grounds that it was “prohibitively expensive.” He was later fired after accusations of “trying to benefit his private business with proceeds,” according to the Orlando Sentinel.

Because no museums would take on the financial risk of hosting “Son of Heaven,” private backers who’d been promised record-breaking crowds looked to recoup their investment in any way they could. This manifested for some in counterintuitive ways. Per Columbus Monthly, Halvorson “seems to have brokered the early funding for the exhibit through a San Leandro, California, charitable group [for health services] known as the Vesper Society… Both Vesper and [another organization, Resource Center for the Handicapped, of which Halvorson was chair] are beneficiaries of the Son of Heaven exhibit and, particularly, retail sales profits.”

“If not for the last minute, nothing would get done” is a cute aphorism, but it seemed to plague “Son of Heaven” planners at every stage. Early in 1987, Ohio’s Department of Development was champing at the bit for a bold new economic driver; it shopped around in its larger cities for a base until space, transit options and timing eliminated all but the capital. As the exhibition was announced, the city had not yet actually secured the purchase of the Central High School building, much less its redesign and renovation. The search for a third host, expected to launch its showing in March 1990, continued even the Columbus run ended in November 1989. Meanwhile, candidates eyeballed the ROI and decided the security, fire code, parking and traffic problems weren’t worth the hassle. Not even Disney was willing to kick in financial backing, despite the exhibit’s prestige and rapturous reviews.

“Orlando could have suffered a major embarrassment if the rush to stage the show had produced a botch,” the Sentinel wrote in January 1990. The show’s organizers “wanted America’s tourist capital to rescue them, and on short notice. That’s not the way, or the reason, to stage an exhibition.” Yet because Orlando had submitted a letter of intent to host, one organizer asserted, Son of Heaven Inc. had dropped its negotiations with other cities — leaving the corporation holding the bag, with nowhere to go but home.

The thing about diplomacy

The Americans were, of course, not the only parties to what became of “Son of Heaven.” If you have an hour, you can admire gallery highlights and educational patter in this video presentation, shot in Seattle and on location around China. It’s anchored in a very particular moment in history, as this narration shows:

“Until modern times, China was isolated from most of the rest of the world. Even today, knowledge of China in the West is often superficial and fragmentary. To understand what is happening in China today, it is essential to understand the Chinese past.”

It continues:

“The greatest treasures of imperial art have been unavailable in the West, and the Chinese themselves have demonstrated little inclination in previous decades to focus attention on the very imperial system their revolution had overturned. In recent years, however, the Chinese authorities have begun to send exhibitions of cultural relics abroad to great acclaim around the world.”

The antiquities spotlighted in “Son of Heaven” spoke for themselves, but they were not apolitical. Seattle’s modest turnout proved particularly troubling for producers, despite the city’s sizeable Asian population. A member of the Washington state senate attended its opening, but not the mayor — a reflection, some speculated, on Seattle’s Chinese diaspora coming mainly from Taiwan. “It is the People’s Republic that sent the exhibition — and numerous government officials to the opening,” observed Columbus Monthly — “and is getting $1 million in fees plus 11 percent of the gift store revenues.”

“Son of Heaven” opened in Columbus on March 1, 1989. Just three months later, Chinese troops fired on pro-democracy demonstrators at Tiananmen Square in Beijing, with a death toll that’s still in contention today. The only protests at “Son of Heaven” for which I have proof are by advocates for the homeless, who resented city and state spending on the spectacle. I’ve seen some tantalizing anecdotes that Chinese curators and workers affiliated with the exhibition sought asylum after the June 4th Incident, but nothing concrete. The Orlando Sentinel speculates that staffers in China were caught up in the pro-democracy movement one way or another, which created delays in approving extension requests that doomed the exhibit’s American run, but offers no evidence.

“Orlando has no business helping the People’s Republic of China save face,” the Sentinel announced in its January 1990 report on the hosting deal’s collapse. “The Chinese decision to allow the artifacts to remain in America almost certainly proceeded from the hope it might restore squandered good will. Also, China would have reaped a fee of $400,000.” While solidarity seems like a negligible factor in the demise of “Son of Heaven” compared to its producers’ profound mismanagement, the stance is interesting to observe from 2024.

China’s own line of emperors also ended ignominiously. And yet: the emperor is not really the focus of “Son of Heaven.” Consider how Robert Thorp, the American of the two lead curators, extols the Terracotta Warriors, four of which sojourned in Columbus: “We want you to be able to look at each individual face. Every face, every horse, is different. Every one reflects individual hand modeling and finishing. There are probably altogether some two dozen different facial types represented among the army of soldiers. But again, every mustache, every beard, every bit of facial detail is absolutely different, because every one is an individual’s creation.” As one 2006 New York Times travel feature notes, “The most important artist in Chinese history was ‘anonymous.’”

The creators of the artifacts that comprise “Son of Heaven” were doing so for the glory of the ruler, yet that glory is a memory now and the staggering artistry, sensitivity and craftsmanship of these objects endure. Thirty-five years is a heartbeat to the timeline of Chinese empire, but I still remember being a little girl, enraptured by the life still evident in one jade disk carved in the Eastern Han era, two millennia before me. ✶

Do you remember the “Son of Heaven” exhibit? I would love to hear from you! I’m particularly interested in stories from attendees who are members of Chinese diasporas from smaller or more isolated communities. (I grew up Jewish in Appalachia, I get it!) I’d also love to hear from anyone who worked on the exhibition in any capacity, from selling tickets and sweeping floors to conserving artifacts and wrangling logistics. Please reply to this email or write to esther.bergdahl@gmail.com to be in touch.

I highly encourage visiting OSU’s Knowlton School of Architecture Digital Archive for wonderful high-resolution photos of the design, construction and presentation of the exhibition in the old Central High School building on the Scioto River. You should also check out the Columbus Dispatch’s retrospective gallery, which has some fantastic portraits of visitors of all ages.

What’s an artifact or exhibit you’ve seen that made a big impression on you? Let me know in the comments or on Bluesky. I love recs and growing my teetering to-visit list.

Thanks for reading Excited Mark! If you’d like to support my work, please share, toss a few bucks at my Ko-Fi or become a subscriber, free or paid. I’m also available for hire as a fact-checker, editor and journalist — visit my RealName.com for clips, services and more.

Get Excited About: Cdramas, Xianxia and Chinese Media

We all have that TV show that got us through lockdown — at least, I hope you did. I wouldn’t have made it without my dog and the online community I found that got utterly deranged about xianxia disaster hotties.

I am from Orlando and I absolutely remember seeing that jade suit at the Orlando Museum of Art. Googling shows that an abbreviated version of Son of Heaven went on tour a few years later, "Imperial Tombs of China", which came to Orlando in the summer of 1997, looks like? I wonder if this is related to the Sun of Heaven exhibit fiasco...I remember something about being disappointed that the Sun of Heaven exhibit never made it. However the "Imperial Tombs of China" was not a "blockbuster" exhibit, and at the time, the Orlando Museum of Art was not a very big venue. I wonder if there was any relationship to Splendid China, the theme park of "miniatures" that was open from 1993-2003. Seems like any exhibit should have happened there. Hmmmmmmmmmm....what an interesting investigation!