Aesthetic Violence and Why We Love It

The best fight choreography can leave your heart pounding like you've just battled your own mortal enemy.

We’ve acknowledged for a long time now that the Marvel Cinematic Universe has become bloated and boring. But 10 years ago, Captain America: The Winter Soldier made us all drastically reevaluate square-jawed, old-fashioned Steve Rogers. Dropping him into a paranoid political thriller brought out new understandings of both where he came from and what he was capable of — by which I mean holy cats, Captain America can beat the shit out of anyone he wants… except Bucky Barnes.

That fight scene at the movie’s midpoint remains a zenith of the entire MCU. When I had a bootleg on my hard drive, I knew the precise timestamp for my hit of heart-pounding, knee-squeezing, character-driven violence. I’d watch it over and over again, studying the fight choreography, tracking which shot showed the actor and which the stunt double, losing myself in the incredible sound editing. I bet my pupils dilated as my blood thumped in parasympathetic arousal. My experience with self-defense or martial arts is limited to one lunchtime workshop several jobs ago, but when I’m immersed in a great fight onscreen, I feel like I can take credit for it after.

Before I got into c-ent and kdramas, I had a vague impression of wuxia films, of Bruce Lee as gone-too-early icon — Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon or the color-coded splendor of Hero; that decade of “Kung-Fu Fighting” punchlines. I’m easily impressed with fight choreography. When I dug into Avatar: The Last Airbender (the cartoon original, please!), I was so impressed by how the team developed each bending style from real traditions. It hadn’t occurred to me that schools of martial arts could develop like musical genres.

When she felt down, a friend in college used to watch the final 10 minutes of romantic comedies, speed-running the big confession and resolution. For me, nothing does it for my mood like the Battle of Helm’s Deep. I love catharsis, sure, but I love it even more when it’s violent. Obligatory caveat: I haven’t been in a physical fight since first grade, when I slapped a boy at recess —someone I had a 6-year-old crush on! — for being mean to my best friend (rumored — sorry, Aaron).

I can do this all day

Forget the Acura ad. Forget every time you’ve heard it too often. Sit down with a good sound system or pair of headphones and listen to “Voodoo Child (Slight Return).” The virtuoso triumph of Jimi Hendrix fully feeling his power, in total communion with the Experience, the most alive a person can be, does what a perfect fight scene does to me. Slot that into a narrative and make the fight do storytelling and I’m simply vibrating on a whole other level of investment.

Take Kim Geon-woo (my beloved Woo Do-hwan) in Bloodhounds, a sharp, brutal eight-episode Netflix kdrama. He’s a former marine who competes in boxing tournaments to support his mother; he’s also the sweetest, purest soul in the Asia-Pacific region, a phenomenal counterpart to best friend/brother-in-arms/chaotic mouth-runner Hong Woo-jin (Lee Sang-yi). Both were about to start their lives in the civilian economy when COVID-19 shut down the whole world. Predatory lenders swooped in to “save” Geon-woo’s mother, who runs a modest cafe in a poor part of Seoul. Here’s what happens when a gang of suited thugs comes to collect on her loan.

This is a magnificent fight in isolation; real boxers in the YouTube comments lavish praise on Woo Do-hwan’s footwork and form. To know that Geon-woo is a justice-minded mama’s boy who cares about “the heart of a boxer” above all else puts the shocking power and efficiency of his attacks in delicious contrast. Zoom out and see how the scene supports the big picture: “Bloodhounds examines how fighting a system as warped and massive as capitalism leaves little room for keeping one’s hands morally clean,” writes Kelcie Mattson for Collider. “Hard-won survival doesn’t have easy exemptions for those with good hearts. Bloodhounds is optimism at a cost.”

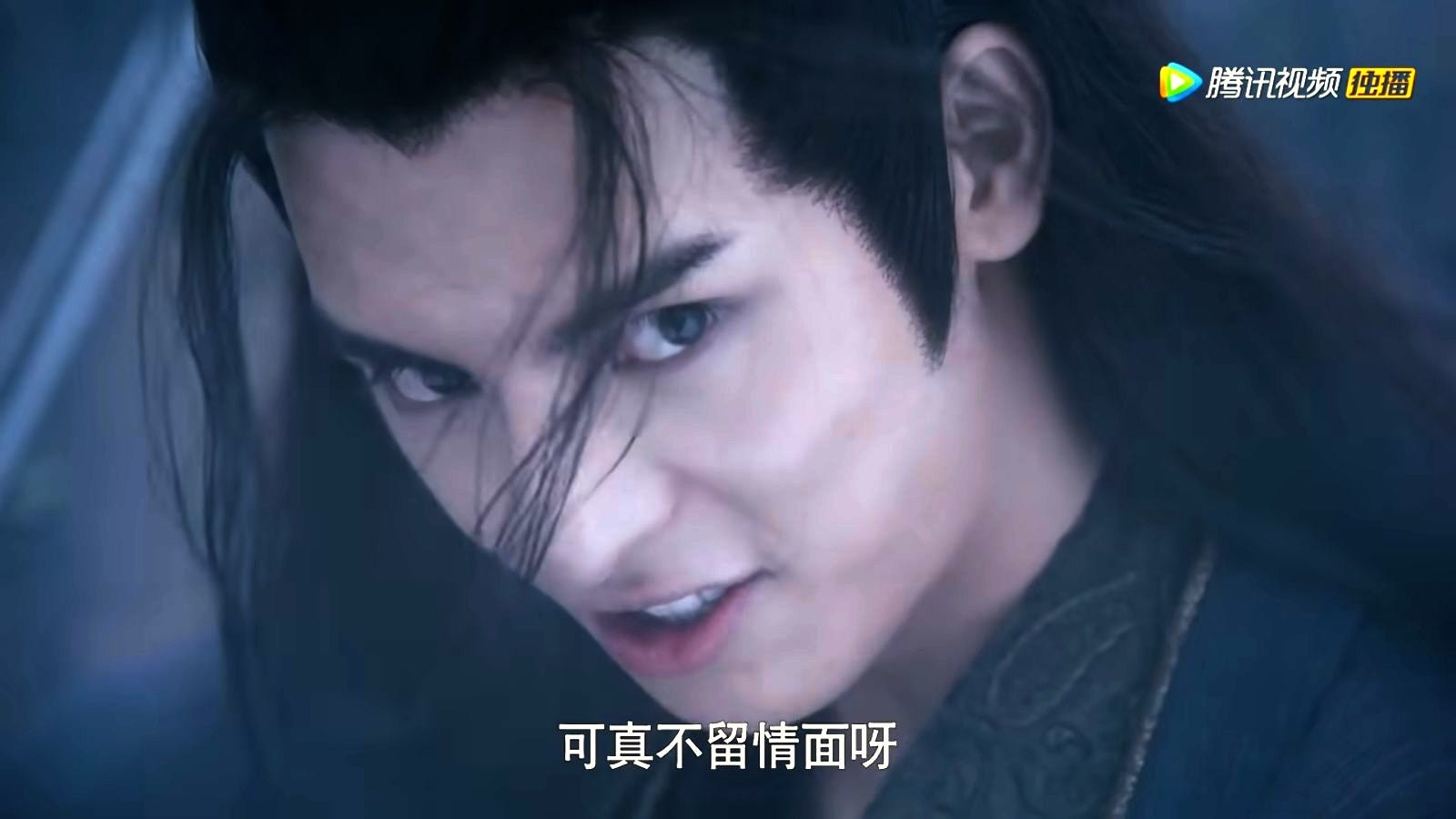

Fights that advance the plot also carry a special frisson. In My Journey to You, assassin Yun Weishan (Esther Yu Shuxin) infiltrates a martial arts sect as a bride candidate. Prior to facing off with Jin Fan (Sun Chenyun), her betrothed’s loyal bodyman, no one knows she can even fight. Watch what she gives away by engaging — and how she maintains her cover.

Truth, justice and the way of the fist

Like many of the most gifted onscreen fighters, Esther Yu has years of dance training. Here she is rehearsing for the above sequence; here she uses incredible strength and flexibility in a muddy battle royale against other female assassins. That dancers make some of the best stage warriors comes as no surprise: the history of martial arts has always been closely tied to theater, acrobatics and entertainment.

In China, archaeologists have identified bronze vessels from the 11th century BCE decorated with figures practicing recognizable martial arts. However, much of what we’d identify as martial arts in film and TV derives from a more recent stew of influences. Fight choreographers of Shanghai’s early film industry learned their trade from Peking opera and folk arts. The Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901) looms large in the background, and it can be hard to untangle how much of the venerated ancient past is actually Republican-era propaganda.

That’s not to say martial arts today is all marketing. In China, philosophy and religion run deep in formal combat. “The moves and routines of martial arts follow the thinking mode of Taoism,” write Baojun Chu et al. “For example, the moves of Tai Chi emphasize the need for remaining motionless and waiting for motions of the enemy, and most of its moves consist of attacking first and defending later.” By imbuing violence with concerns of justice and even Chinese national character (as in personality, rather than nationalism), you get the literary xia conceit of a wandering paladin. It’s also a good way to get your project made. Chu et al again:

“Adding ethical ideas to the violent content shown to the audience beautifies the presentation form of inappropriate elements in the violent picture and is a kind of digestion of violence. By presenting the violent elements in films with violence aesthetic in the form of martial arts, it has the characteristics of information ethics, which is conducive to reducing the negative influence brought by films with violence aesthetic and strengthening the adaptability of films with violence aesthetic under the Chinese film and television system.”

Neuroscience as mysticism

Let’s dispense with whether enjoying violent media makes you violent (it depends, though martial arts training probably makes you less aggressive). The neuroscience of violence — heck, the economics of violence, if we call it inquiry into choice-making — is fascinating. One study found that experience matters more than reaction time in relation to “perception, cognition and action in combat sports,” and that experts rarely take their eyes off their opponent’s “central pivot (head and trunk).” Another examined the Japanese concept of mushin, a martial headspace marked by “complete awareness without the shackling of conscious thought.” The researchers found a plausible neurological basis for what guides ideal combat.

Taisen Deshimaru, a Japanese Sōtō Zen Buddhist teacher who founded the Association Zen Internationale, wrote in response to a question on how to choose the technique of attack: “There is no choosing. It happens unconsciously, automatically, naturally. There can be no thought, because if there is a thought, there is a time of thought and that means a flaw. For the right movement to occur, there must be permanent, totally alert awareness of the entire situation. That awareness chooses the right stroke; technique and body execute it… Think-first-then-strike is not the right way. You must seize upon suki (gap or opportunity).”

I think my favorite study comes from Dr. Victoria Lagrange and her team at Indiana University. They looked into who makes violent choices in interactive fiction, which can be as complex as a graphics-intensive video game or as simple as a Choose Your Own Adventure paperback. “We suggest that by choosing high violence, people claim specific forms of agency over the media content, which leads to greater enjoyment,” they write. “The appeal might not be the satisfaction of a disposition, but rather an act of choosing stories that break out of the ordinary and thus open up an aesthetic zone of enjoyment. Choosing violence is enjoyable, not violence itself.”

For all the science underpinning violence, however staged or controlled, there is still something mysterious about an excellent fight scene. It’s not just the enthralling combination of grace, speed, narrative, emotion, power; in historical Chinese stage combat, writes martial arts scholar Dr. Ben Judkins, “the actors on stage were often viewed as being ‘possessed’ by the ‘ghost’ of the historical character that they portrayed. To watch a traditional opera performance was to enter the world of the supernatural.”

Mama said knock you out

Many of the papers I read for this essay were deeply, almost performatively concerned with whether enjoying violence, especially by making it artful, indicates some kind of moral flaw. “The aesthetics of violence is meant to dull the violence and brutality of violent acts,” asserts one group of scholars, “and its trajectory is to depart from violence and sail toward beauty.”

I tend toward a neutral/fascinated view of martial brutality. Narratively, a fight is a crucible that reveals the indivisible parts of someone’s character. I don’t mean this as some sort of Hobbesian pessimism or a nihilist belief that violence is who we are. To watch a person protect themselves inside a story is to understand how they respond to the world. Whether they attack or defend, whether they’ve trained with a weapon or they’re just lashing out, we see into them at a moment when everything is on the line. Mushin takes over. That kind of distillation is exactly what pulls us toward art.

Bobby Talbert, a stuntman and fight choreographer known for the Fast and the Furious franchise, says simply, “A great fight scene or stunt scene should be a beautiful demonstration of the physical action that represents the psychology of the character.” We feel different things about other kinds of violence — gore, abuse, torture, terror. Violence between equals, though, kicks the knees out from narrative certainty. Who’s going to win? If the two parties are worthy opponents (physically, if not in virtue), what will tip the scales? What keeps them alive? How are they still alive?

Do you feel that? ✶

Have I missed the best-ever fight scene? Let me know in the comments or on Bluesky. I love recs and growing my teetering to-watch list.

Important boilerplate for the people

Thanks for reading Excited Mark! If you’d like to support my work, please share, toss a few bucks at my Ko-Fi or become a paid subscriber. I’m also available for hire as a fact-checker, editor and journalist — visit my RealName.com for clips, services and more. Most appreciated!

SO fascinating! I loved your investigation and examples...honestly it's been too long since I watched Winter Soldier, that scene had me holding my breath! But the most valid point you made is that we really should have gotten a LOT more Liu Haikuan fight scenes!