The Most Famous Boy in China

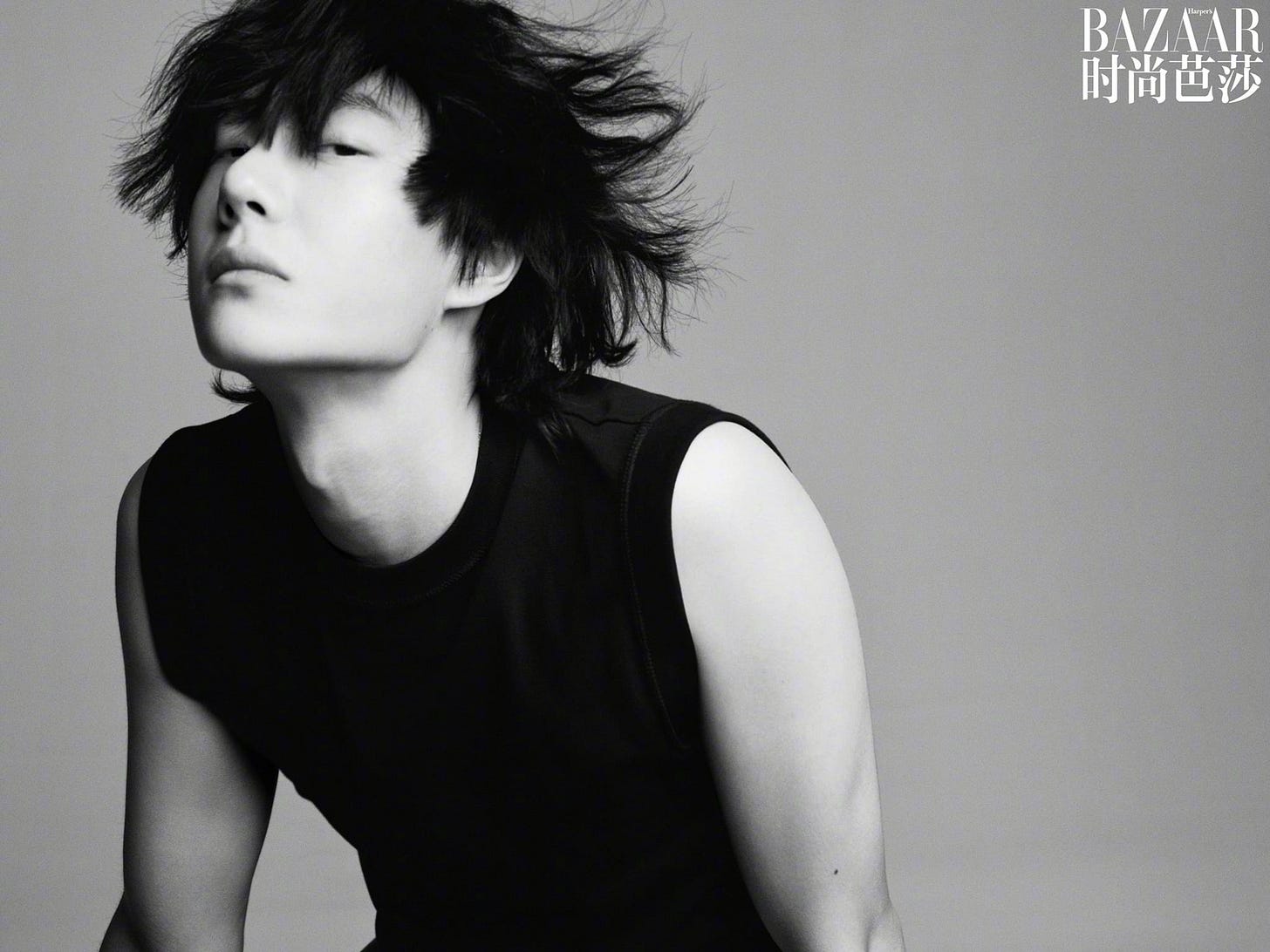

Stardom has changed a lot since Wang Yibo, 27 in August, first set out to embody it.

For at least a decade, Anglophone thinkers have lamented the death of selling out. Gen Z especially (so received wisdom goes) no longer cares that mega-corporations dictate, platform and extract profit from every means of social status and human connection — it’s the old saw about a fish asking “What’s water?” This is just the world they know, and being an iconoclast isn’t for everyone.

Maybe there’s still an argument to be had in the English-speaking world about selling out, in this economy. China seems well past that stage. Fandom there entails staggering levels of consumerism, as idols endorse luxury goods (or whatever partnerships they can swing) and fans clamor to support their careers by moving as much merchandise as they can. There’s even a term for the top shakers: liuliang celebrities, whose highly motivated fan bases are a selling point in themselves.

The numbers don’t lie about the most in-demand stars. Xiao Zhan is always at or near the top of the pile; other reliable contenders include the Uyghur actress Dilraba Dilmurat, surviving Word of Honor lead Gong Jun and a slew of athletes, following the Beijing Olympic Games. Perhaps the most interesting of them is also one of the most successful — not just financially, but artistically, athletically and politically.

I’m going to tell you a series of facts. Wang Yibo was born one month to the day after my bat mitzvah. His hometown, the city of Luoyang, boasts more than 4,000 years of history. As a child, he was ill with a rare and serious disease called myocarditis. He became a k-pop trainee and spent his high school years in Seoul, away from his parents. He’s both a shareholder in his management company and a major source of its overall revenue. He was nominated in his big-screen debut for a Golden Rooster Award opposite international legend Tony Leung — the equivalent to an Oscar. He is an honorary firefighter and a professional motorcycle racer. He cannot cook to save his life.

Now I’m going to ask you to watch him move.

Little fresh meat

There’s this term in c-ent, xiaoxianrou. The gender scholar Gene Song writes that “‘little fresh meat’ significantly reverses the ‘male gaze’ to portray men designated as inexperienced in sex and love (‘fresh’) and in possession of a young, healthy and desirable body (‘meat’).” They “represent a new fashion of male embodiment — characterized by a trim physique, flawless skin, stylist haircuts and attractive facial features, sometimes enhanced by makeup.” One signifier is “the A4 waist”: “a social media trend … in which people, mostly women, post pictures of themselves holding a piece of A4 paper vertically in front of their torso to show that their waist is narrower than the paper’s 8.3-inch width.”

Many analysts tie the popularity of the little fresh meat mode of male celebrity to the increasing economic power of young women in China and across Asia. The aesthetics of the Korean kkonminam (flower boy) and Japanese bishōnen (beautiful boy) are not just transnational but globally appealing. Song even writes that Confucian tradition “makes the bodily rhetoric less subversive for the hegemonic gender order”:

“Historically in China, for example, women have always been attracted to men of letters whose civilized and gentle demeanor emanate their promising future in studies and then politics. Such frail-looking men were seldom faulted for lacking in masculinity, as they enjoy routes to power other than brute physical force.”

Let’s be clear: debut-era Yibo is not an elegant scholarly type, exemplifying wen masculinity in opposition to the more martial wu variety. In his role as the rapper and main dancer for the Korean-Chinese boy band UNIQ, he’s both brash and babie. This persists in the affectionate teasing with which his Anglophone fans discuss his various body parts: his unmistakable cheeks are yeekies, his profile is defined by his yose. When Yibo strikes out on his own, however, his self-presentations become far more complex.

The Second Jade of Gusu

The Untamed, a queer love story adapted within inches of plausible deniability, was Yibo’s first period drama.1 Five years after its release, fans and tinhats alike are still obsessed with his chemistry with Xiao Zhan. Yibo’s bratty adulation of his co-star is as charming as his character’s early furious, simmering desires. Fans of the live action show cover for Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji’s love story (quite explicit in the original Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation novels) by referring to it as “socialist brotherhood.” Fans and anti-fans of the actors’ CP (coupling) literally brought down a major hub of international fan culture within China and almost destroyed Xiao Zhan’s career.

Hong Kong University’s Gene Song again:

“[D]espite the popularity of ‘little fresh meat’ images, BL [boys’ love] content has to be reduced, regulated and controlled, because … women’s obsession with danmei is treacherous to both the state and the patriarchy, as it touches on ‘all possible taboo[s] in current China’: homosexuality, the objectification of men, pornography and infertility.”

Still, Yibo thrived after The Untamed. His endorsement deals mushroomed to include the likes of Chanel, Audi, LaCoste, eyeglasses designer Helen Keller (I know) and makeup brand Shu Uemura. He threw himself into skateboarding, street dance, motorcycle racing, more dramas. For three years after The Untamed, he was still on co-hosting duties for the massively popular talk show Day Day Up. “Yibo is very talented,” says one of his racing teammates in a 2022 documentary. “The only thing he lacks is his lack of time [sic]. He doesn’t have much time.”

“I don’t have a lot of time,” Yibo agrees, “because every time I go out, it becomes other people’s time.”

Soft power versus the other kind

Notwithstanding how much money Yibo makes for himself and his sponsors, the makeup-wearing, gender-playful, cutting-edge boys of Chinese pop culture have not been universally embraced. Right from the start, an outcry rose up against “niangpao,” which Sinologist Kam Louie writes is “literally translated as ‘lady cannon’ but more commonly and idiomatically rendered as ‘effeminate man’ or ‘sissy.’” This coincided with “the political rhetoric in China relating to almost every aspect of life [becoming] increasingly more doctrinaire and unyielding”:

“While the condemnations of the niangpao and the responses to them are ostensibly about what constitutes correct male behavior, the vehemence with which they are expressed betray a much deeper insecurity and bewilderment about the role of Chinese men in a rapidly changing world. This panic about fast-changing gender roles can be seen in the claim that if Chinese men are feminized, it would lead to the demise of China itself.”

A series of bans came down on celebrities and citizens alike. They hit portrayals or glorifications of “effeminate men” in September 2021, relegating many BL dramas still in production to deep freeze. A number of little fresh meat stars found themselves booted from society, whether for actual crimes or by social media campaigns. One conspiracy theory even alleges that k-pop, j-pop and other modes of entertainment are a long-running CIA plot to weaken the Chinese state.

Of course, Louie writes, “[a]nyone who has seen performances by the emblematic xiaoxianrou boybands of East Asia will know that these boys are anything but feeble. They are usually extremely athletic and can do very complicated and physically demanding dance routines. … They are ‘girly (niang)’ only in the sense that women are generally more supple and vivacious, certainly not brittle and dull.”

Wang Yibo comes alive when he’s dancing. I’m in awe of the power, precision, strength and discipline it takes to move like that, much less to find primal joy in the art. He still dances, as when he’s executing massive performances or learning how hard Peking opera really goes. Lately, his grace has turned toward fight choreography — and don’t get me wrong, I love that stuff. Yibo’s nasty, hand-to-hand battle with Tony Leung in Hidden Blade is some of the most electrifying, character-driven violence I’ve ever seen. It’s just that the venues for Yibo’s gifts have been trending patriotic — something, something, selling out? Something, something, what is water?

Hidden Blade is a riveting, unsettling spy drama set during Japanese occupation in the late 1930s and 1940s. The recent series War of Faith takes place early in the Great Depression, when it’s still treason to be a communist. Last year’s mega-grossing air force flick Born to Fly is a rousing Top Gun-style flex. Being a Hero is an undercover cop show about fighting drug trafficking. Faith Makes Great is a star-studded anthology that “chronicle[s] the people’s endless struggle to realize their dream of rejuvenating the nation.” Even in the realm of endorsements, Yibo was among the celebrities who cut ties with high-profile global brands like Nike and Calvin Klein, accused of “smearing China” during an outcry about forced labor for Xinjiang-sourced cotton.

Palpable anxieties for ???? threats

Early in their professional relationship, The Untamed co-star Xiao Zhan (six years older, but much newer to being an idol) often called Yibo “Lao Wang” — Teacher Wang, who’d been in the entertainment industry since he was 13. Yibo’s longevity in the business speaks to a keen understanding of audience and state demands. The way he navigates masculinity is central to both.

The switchover from little fresh meat among male idols to something harder, more wu,2 happened with shocking speed. “Increasingly, the expression ‘if the youth are strong, then China will be strong’ has become a rallying cry for those who see ‘sissy men’ as symptomatic of the decline of the nation,” wrote Louie earlier this year. However, the preferred alternative is not so simple as being assertive, sweaty, militaristic or gruff. As Louie continues, “commentators have often pitched ‘soft masculinity’ as a desirable characteristic in a man… Inevitably, in examining Confucianism and masculinity, the roles of father, husband and son demand attention.”

For all his tough or cool guy roles, Yibo takes on other facets of masculinity too. He himself is often sweet, earnest, dopey or goofy. In the period spy thriller Luoyang, set during the Zhou dynasty (690-705 CE), Yibo plays the second male lead, Baili Hongyi, who is both useless in a fight and forced into an arranged marriage when he would really much rather think about puzzles, fine dining and city works.3 The delightful Legend of Fei sees him as Xie Yun, a smartass wanderer with a hidden identity. It’s the closest I’ve seen him come to examining his own disability in his work — his experience with heart failure as a kid. When offered black-and-white options, both characters choose a third way of relating to who and what they love.

In public, Wang Yibo plays himself extremely close to the chest; you’ll notice how many of his roles are about disguise and deception. Especially as an American outsider from the wrong diaspora, I have no insight into what he buys into and what he merely uses to do what he wants. I like to think he gives us clues from time, though. “I don’t like hitting the beat all the time,” he tells another dancer in the documentary series My Legacy and I. “I like using the rhythm of my body.” He’s worked enormously hard over much of his life for the privilege of pursuing his interests like he does. I hope he keeps playing these games on the terms he wants. ✶

Important boilerplate for the people

Thanks for reading Excited Mark! I’d love to hear from you about this essay and this project overall. If you’d like to support my work, please share, toss a few bucks at my Ko-Fi or become a paid subscriber. I’m also available for hire as a fact-checker, editor and journalist — visit my RealName.com for clips, services and more. Most appreciated!

Yes, I am omitting his bit part in A Chinese Odyssey: Part Three, although the red hair and celestial tops/rollerskates?? are pretty delightful.

Furthermore, I acknowledge that “The Second Jade of Gusu” is a fanon epithet, not canon. It makes for a good subhead, though.

This is an affiliate link to Bookshop.org, for which I get a small kickback if you buy. For a good time, check out more of my recommendations here!

Many of Yibo’s roles are decidedly neurospicy, among which his special interests include accounting, engineering, street dance and Wei Wuxian.