Back When Tigers Used to Smoke

It's been a century since the last Korean tiger was killed off, but in stories and other art forms, they're indelibly linked to the land and its people.

One of my favorite daydreaming games is to choose daemons for my best-beloved fictional characters. If you grew up obsessed with Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials books (otherwise known as Paradise Lost for kids) and their associated ventures into film, stage, radio, comics and television, you too may long for a shapeshifting animal soulmate that talks. It’s such a beautiful shorthand for revealing character. I’m convinced, for example, that Steve Rogers of Captain America fame would have a sparrow daemon, something that’s breakable, scrappy, audacious and resilient.

My curse, of course, is that I can never figure out precisely what my daemon would be. All I know is that I love every dog, and that every creature I try on for size doesn’t quite feel right. It’s another reason why I have no tattoos, even though I’m delighted by everyone else’s, and probably why I never became a furry. Go back even deeper into my past and I couldn’t decide which Redwall beast I would be, a fun-loving otter or a talkative hare. The one moment I experienced certainty about self-identification and animals came when I was 7. A potent combination of Racso and the Rats of NIMH and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles revealed to me my true dream of becoming a person-sized punk were-rat. (The early ‘90s were mondo tubuloso.)

Thus I envy and admire people who know which animal best represents them. This gets really fascinating to me when it expands to cover groups, whether it’s a sports mascot or a national symbol. (For a wild medley of both, watch Animalympics, one of those odd ‘80s fever dreams that also was weirdly formative for me.) There’s a heraldry to these creatures: the Russian bear, the Spanish bull, the American eagle, the British lion. Learning about national animals that are new to me is also a delight: the Komodo dragon for Indonesia, the stork for Lithuania, the tapir for Belize.

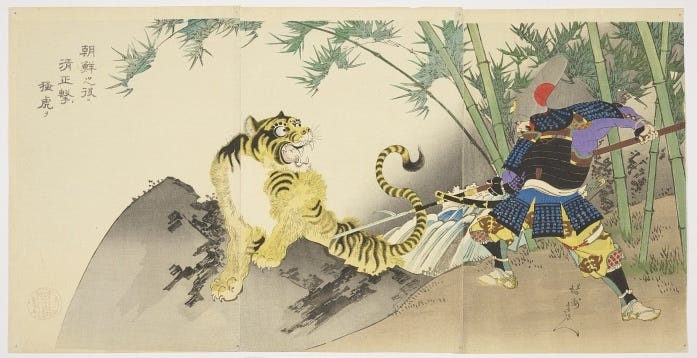

Around the turn of the 20th century, a Japanese geographer remarked that the Korean peninsula looked like a rabbit, its long ears folded along the northeastern coast and its timorous paws clutched northwest of the capital. In 1908, the anticolonialist intellectual Ch’oe Namsŏn fired back: Korea was and always had been a tiger.

This wasn’t just posturing — Koreans’ relationship with the tiger goes deep into prehistory. They served as guardian spirits, amused as folk tales, incited mass panic as devourers and hunters, and they have become most treasured now that they’ve been gone a century. When tigers show up in kdramas, study them a little closer, because something many-layered and powerful is happening onscreen.

King of a Hundred Beasts

The tiger is a showstopper by nature. We don’t see them as often in kdramas as, say, foxes and their nine-tailed counterpart, the gumiho. They absolutely know how to make an entrance, though. The video above shows an abridged subplot from Hotel del Luna, in which the ghost of a poorly taxidermied North Korean tiger must find peace so it can stop haunting Seoul. In Lovers of the Red Sky, the mountain guardian Ho Ryeong appears as a composed and ferocious girl to protect our heroine from the demon Ma Wang; she fights him in the form of a blue-eyed white tiger. My theory about the terrifying Bulgasal is that we mistake them for monsters, with their golden eyes, black claws, lust for human blood and uncanny stealth and strength, but they are actually tiger spirits whose mountain suffers from human encroachment.

Tigers star in the first-ever stories about the Korean people. The founder of the kingdom of Gojoseon, more than 4,300 years ago, was the demigod Hwanung, who came down from the heavens and established the city of Sinsi on Mount Taebaek. At that time, a tiger and a bear sought to become human and join that society. They prayed to Hwanung, who promised their wish would be granted if they could stay underground and avoid sunlight for 100 days, eating nothing but garlic and mugwort. The tiger could only endure three weeks of this and fled back into the wilderness; the bear was transformed into a woman named Ungnyeo, who married Hwanung and gave birth to the first human prince of Gojoseon, Dangun.

I like that this myth casts the tiger as something that came so close to being human, who once and perhaps still does envy us, which knows enough about us to truly terrify. Anthropologists have suggested that contrasting the tiger and the bear echoes different strains of totemic shamanism present in the Korean peninsula. Folk religions cast tigers as mountain gods or messengers thereof — the Sanshin, whose favor was maintained at dedicated shrines or freestanding altars. Tigers also appear in many minhwa paintings, popular art for nobles and commoners alike that could protect a household from evil spirits. People relied on tigers in the world precisely because they were such a bad fit with humanity.

Furthermore, the feared and venerated tiger can’t be taken too seriously all the time. To (more or less) paraphrase G.K. Chesterton, it’s crucial to know that a tiger can be defeated. In art and parables, magpies often fool or humiliate tigers, whose nobility can flip into gullibility. One story relays how a tiger gets stuck in a mud puddle for three days, and after it begs a friendly woodcutter to save it, the tiger tries to eat him. The woodcutter tries to enlist an ox and a pine tree as witnesses or jury, but they each agree: the tiger should get its meal. Finally, the woodcutter turns to a magpie, who suggests they reenact the scene so it can decide fairly. The tiger gets stuck in the mud all over again, and the magpie has been a friendly helper to humans ever since.

One of the coolest folk traditions I’ve encountered through kdramas is pansori, a kind of epic poetic storytelling form with a singer and a drummer. Only five performances have survived to the present from the Joseon era, but one of them is the comedic Sugungga. The Dragon King of the Southern Sea demands that one of his subjects fetch a rabbit from the land, as a rabbit’s liver is supposedly the only thing that will cure his ailment. A doughty turtle volunteers, but when he makes it to land, he’s met by a fight among the land animals about who will take the place of honor at a party. The matter is settled when a tiger descends from its mountain and assumes the seat without being invited.

When it discovers that a turtle is present, the tiger proposes that he be killed and made into turtle soup. First, the turtle insists he’s not a turtle but a toad — less tasty. The tiger attacks, and the turtle stretches out his neck suddenly, scaring the tiger and saving his own hide. In 2019, a modern cover of the Sugungga story cycle by the alternative band Leenalchi became a surprise hit. It turns out we’re still thrilled by the lyrics, in whatever language:

The tiger is coming down, and the tiger is coming down.

To the valley in the deep forest, the beast is coming…It’s opening its red mouth and roaring,

Like the sky fall is falling and the earth is giving way.

Your face on their money

“Back when tigers smoked” is the Korean equivalent of “once upon a time.” As stories, tigers were to be admired; as inhabitants of the land, this admiration didn’t protect them. Twelfth-century records recount a memory that “nine tigers entered the Koguryö kingdom's capital of Pyongyang in 659 CE, devouring an unspecified number of persons before being pursued by hunters,” write Koreanists Joseph Seeley and Aaron Skabelund. Scholar Hyuk-chan Kwon notes that prior to the Joseon dynasty, while the isolated mountain habitats of tigers rarely crossed into the cities where most Koreans lived, geomantic concerns — that is, the auspicious configuration of built and natural environments — kept tigers’ habitats most intact around the royal palace, where they were frequently spotted.

With the Joseon dynasty, however, a series of land-management decisions brought tigers and humans into more and more dangerous contact. The only cause of death more lethal than a tiger was smallpox, and a word grew out of these attacks: 虎患, hohwan — tiger disaster. A special elite force of tiger hunters, called the chakho gapsa (捉虎甲士), grew into the tens of thousands, including riflemen, “beaters, infantry, hunting dogs, cavalry and sometimes even royal guards,” writes Kwon, whose stated purpose was to minimize casualties from tiger attacks. Yet not every king used this cohort justly: “Tigers provoked fear, but the act of causing trouble to innocent people under the pretext of catching a tiger could be even more devastating.”

The myth of Ungnyeo the bear-woman and the tiger who failed to become human was recorded at least by the 12th century, in Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms. Scholarship suggests it may date as far back as the 4th century BCE, and tigers appear in Bronze Age petroglyphs found around Ulsan. For Japanese colonial forces in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, tigers’ deep history and psychosocial presence in Korea made them an overdetermined target for extirpation. Officials framed the tiger as a dangerous predator that presented obstacles to modernity. Tiger hunts also became a status outing more than an act of protection, much like big game safaris elsewhere in the colonized world; in reports, they were explicitly framed as conquests. In 1922, writes Kwon:

A Japanese police officer named Miyake killed the last tiger in Korean history. He then presented the tiger’s fur to Prince Kan’in Kotohito, a prominent member of the Japanese imperial family and a military general. The last tiger in Korea’s official history came to an end as a gift to a Japanese imperial prince.

Within less than two decades of Japan’s colonization, the tigers in Korea that survived the well-disciplined tiger-hunting armies of Joseon for about five hundred years went extinct. To this date, there are no tigers found in Korea’s ecology.

Rumors of tigers persisted throughout the peninsula, especially as Korean nationalists dug into history and literature to rally for their cause. Even after independence, the Korean War and the refugee crisis in its wake further devastated most remaining possible habitats for tigers. Seeley and Skabelund estimate that forests on both sides of the 38th parallel “were reduced to less than 35 to 40 percent of their prewar level.”

South Korea, at least, has moved on without its tigers. They appear as Olympic mascots, characters hawking products and kdrama plot points. Efforts to create “tiger parks” with imported Chinese or Russian Amur (Siberian) tigers have not progressed past the concept stage; “tigers belonged in Korea because they were deemed culturally important,” Seeley and Skabelund write, “not because they had once lived there. […] Nationalism has spurred sympathy for the tiger's plight, but … its limits as a motivation for conservation are apparent.”

One tantalizing possibility for the survival of Korea’s native tigers does keep cycling in and out of fashion: the long, thin nature preserve that’s been effectively untouched for seven decades. The DMZ is four by 250 kilometers, or 2.4 by 150 miles. If you’ve seen Crash Landing on You, you know that the DMZ has lush forests, but as historian Lisa Brady writes, it also “represents a nearly complete set of Korean ecosystems within its boundaries, ranging from wetlands to grasslands to mountainous highland.” Satellite and trailcam images released by Google last year indicate the presence of apex predators like Asiatic black bears (including cubs!). The DMZ’s biodiversity includes species seen virtually nowhere else in their former territory. As Norimitsu Onishi noted for the New York Times in 2004, “It is the only tract of land that has remained intact from before Korea was divided.”

No tigers have been confirmed in the wilds of South Korea, a nation that’s both population-dense and enamored of outdoor pastimes like hiking and mountain climbing. North Korea has not been forthcoming about any tigers either. They may remain in zoos and VFX reels for the foreseeable future, on old silk scrolls and artifacts behind glass. But pay attention to the hairs on the back of your neck when the pansori singer cries The tiger is coming down! In that electricity, they’ve stayed alive forever and longer still. ✶

What’s your favorite kdrama animal? Let me know in the comments or on Bluesky. I love recs and growing my teetering to-watch list.

Thanks for reading Excited Mark! If you’d like to support my work, please share, toss a few bucks at my Ko-Fi or become a subscriber, free or paid. I’m also available for hire as a fact-checker, editor and journalist — visit my RealName.com for clips, services and more.

The Son of Heaven at Central High School

In 1989, a groundbreaking exhibit of imperial Chinese artifacts came to Columbus, Ohio. It was supposed to tour the nation. Then Tiananmen Square happened.

I learned so much! I love that the tiger has such a storied (in many ways) history. The juxtaposition of being feared in life and revered in the imagination is fascinating.