The World Follows Us Wherever We Go

Discovering Chinese and Korean TV was a relief. I was certain I could finally enjoy something guaranteed not to care that I am a Jew.

Heads up: This post deals with racism, genocide, state repression and the Middle East. It is a personal essay; please do not ask it to solve or address every aspect of the most intractable horrors of the century. Look after yourself as you see fit, and thank you for your time and generosity. ✶

I was a girl sleeping in a castle in August 1998. My dad, not given to booking whimsical lodgings, had found a bed-and-breakfast for our Scotland trip that some Victorian built to mimic the Middle Ages. It came with a breakfast nook squeezed into a turret. Edinburgh was clearly a place of wonders. I was 14; I was so excited to be somewhere new in the world; I was having breakfast with my mother.

The man in the full tweed suit was having coffee in the corner, though he was hardly more than arm’s length from us. We were alone with him. I remember his sandy-gray hair, thin but coiffed, and an overbred face: crooked lipless mouth, puffy dark eyes, leathery pebbled skin. He could have been any age over 50. Later, Mom assured me that he said the things he did because he was drunk.

“Ah!” he interjected when he heard us planning our day. “You’re Americans!” He had a posh English accent, Suzy Izzard doing James Mason. He sat facing us, placed perpendicular. My mother and I smiled at this man and confirmed it — yes, we’re from Ohio, it’s my first time here.

“Of course,” he said, still smiling. “But where are you from?”

Surely he wasn’t curious about the intricacies of hailing from Appalachia, but I supplied him, enthusiastically. I bet it was charming: a tall and gangly teenager, her mannered and loving mother.

“No, I don’t think so,” this man said, which was an odd response. “Are you Spanish?”

My mom and I looked at each other. All four of her grandparents came from Lithuania. We demurred and tried to focus on our food.

“Not Spanish, then,” this man announced. “Are you French…? Russian…? Arab? Are you Greek?”

Not until after she died did I realize how similar my mother and I looked. We both have olive skin that tans dark fast, big brown eyes and thick, dense hair. Mine has always been outrageously curly; it fell to my elbows when I was 14. Hers was black, salted in her mid-50s and trimmed short. When we would travel abroad, strangers stopped her in airports to ask directions in a wonderful array of languages. She was not only a monolingual American but deaf in one ear.

“Oh,” said this posh Englishman in tweed, after he’d Rolodexed through enough ethnicities. “You’re Jews.”

His tone curdled, italics on the last word. My mother and I didn’t answer. The next time I looked up, he was gone. I would have cheerfully confirmed if he hadn’t been so weird about it. Sweet, naive kid — I didn’t know what he was asking.

Born in a bottle rocket

You must know about fandom by now, and its abiding love for queer romance. That’s the lingua franca of the community where I grew up online, but for many years, I didn’t understand the appeal. The torrent of fan culture focused solely on men loving and fucking other men felt like celebrating my absence. This wasn’t an escape from a toxic mainstream of compulsory heterosexuality, where value was also rooted in sex appeal and drive. I resented it. Dating was hard enough in real life, and I chafed at feeling like every famous or fictional man I’d ever wanted, admired or idealized for fun would ontologically never reciprocate.

I pressed my friends, many of whom thought they were both straight and women at the time: Doesn’t it bother you, that in our stories, it’s never you who gets what you want? The answer that stuck with me: I guess I identify more as queer than as a woman. Fandom does plenty of its own navel-gazing on this matter, and I’ve heard for years from fans who felt relief engaging with art with no women in it. They didn’t have to worry about power dynamics or misogyny or their own bodies and histories — they could just revel in something that turned them on. Even if I couldn’t quite grasp it, I just had to accept it and do my own thing, which I did, and it was fine.

The first thing I told readers of this newsletter was how The Untamed, a censored queer romance that became one of China’s biggest domestic and international hits, was my life raft during the worst of the COVID lockdowns. It’s what led me to a Viki subscription and to all the cdramas and kdramas I’ve inhaled since. It also opened doors into an incredible fan community, where I’ve learned so much and met many treasured friends.

That first summer, it struck me, the shocked and joyous bark of laughter that comes with some epiphanies: This text has no chance of hating me, I thought. There can be no antisemitism in a Chinese or Korean period fantasy! I guess I identified more as a Jew than as a woman. And sure, would it be cool for a Kaifeng Jew to show up in a xianxia story? Would I totally watch a multilingual drama set in Republican-era Harbin? Yes! But at least by this absence, I didn’t have to fear erasure.

Where I grew up, almost no one looked or was raised like me. When I came to cities like New York and Chicago as a resident, I found the expectations around Jewish life baffling and alienating. In Chinese and Korean TV, I was a stranger and a guest, and I relished that. If these stories were to wound me, they wouldn’t do so by leaving me scrambling for crumbs, or destroying a fascinating and expansive concept for one more universe ordered by a Christian lens. Yes, there’s a weird philosemitism thing in East Asia about the Talmud, and sure, a decade ago, the indices of antisemitic beliefs in China and South Korea were not great, and I’m not sure how that’s progressed. Here, though, I earnestly thought I was free for a while.

Be the happy phantom

My first political cause, the first I chose or fell into on my own, was the Free Tibet movement of the late ‘90s. This would have been the year after Scotland. The phrase cultural genocide weighed so heavily on my imagination, that a people could be destroyed without killing everybody. Later, I read The Jew in the Lotus, a true story about a band of rabbis who traveled to Dharamsala and met with the Dalai Lama, who wanted to learn more about preserving culture in diaspora. That felt so right to me — yes, yes, let’s help everyone stay alive, let’s reject monocultures and respect autonomy and be curious, let’s talk. That’s the best of us.

I’ve heard Jews and Native Americans both grit their teeth and laugh about being someone’s first, about having to explain we’re still alive, we’re still here, we’re whole people taking up space in the same present as you. I don’t know why I was startled, then, when I found a Tibetan actor in a cdrama cast list. His name was Pema Jyad, also known as Ban Ma Jia, and he plays a sprightly servant in a charming xianxia romcom called Ms. Cupid in Love.

A character doesn’t get much more stock, and Jyad does what he can with the role. I found myself wondering about him long after I’d finished enjoying the leads (one of whom virtually recycles his role from The Untamed, bless him). Jyad graduated from the most competitive department (acting) of the incredibly selective Beijing Film Academy. He seems to have had luck making movies — he’s listed third in the 2020 feature Hua Mulan, not to be confused with the live-action Disney film. I want to ask so many intrusive questions that I haven’t earned: What do you think of it all? What’s been your experience?

I started to notice other names in c-ent: Nazaket Mehmut, better known as Jia Nai. Gülnezer Bextiyar, popularly Nazha. Dilraba Dilmurat, mostly called Dilireba. Omid, sometimes rendered Ou Mi De. They come from places like Ürümqi and Kashgar, where even the historic seats of Xinjiang — East Turkistan — can be three-quarters Han. Uyghur actors and models are a hot commodity, according to one industry insider, because Chinese media trendsetters are “looking for [faces] that have some Asian characteristics but also have some kind of white Europeanness to it.” It’s a cosmopolitan aesthetic, as international as Hallyu but fully fluent in Mandarin.

One of the other first things I said in this newsletter was: “We honor the art by seeing the big picture. I don’t believe in punishing creativity because of a creator’s shitty government.” But what I know about Uyghurs is Potemkin social media, transnational repression, missing family members, high-tech mass surveillance, a diaspora in dire straits, language extinction, forced labor, residential schools, concentration camps.

How does one make a career in the context of such horrors, other than by having no choice? How do you get up every day and shoot an ad for Fendi, play an eagle princess in hanfu or a cute romcom professional or a glowering henchman, dance on a reality show, defend Xinjiang cotton?

The state tells us that everything is fine and the intimidated West is racist against multinational, multiethnic China. This is not my diaspora or my metropole, and I know how sick I am of being hounded about the worst things done either to or by people of my ethnic group. I go about my day as an American while my government benefits from slave labor, fails asylum-seekers and pits them against disinvested neighborhoods, sacrifices its children and citizens to the gun lobby, chooses its voters and ten thousand other structural crimes. Look: I’m even writing about Uyghurs and Tibetans while trying to make readers see me.

There is something awful about the silence, though. We ramble nervously to fill it. Scholars have no answer and neither do we. Yet if Dilireba told me I was talking out my ass, my foolish American heart believes a perfect world means I could take her retort at face value.

Since I’ve gone away

To me, the best back-of-the-napkin definition of antisemitism comes from Yossi Klein Halevi, who grew up a militant Kahanist but later turned to interfaith peacemaking. Antisemitism, he says, is “the process by which Jews are turned into The Jew, and The Jew becomes the symbol for whatever a given society or civilization regards as its most loathsome qualities.” This is why antisemitism can be about polluting blood and/or killing God and/or subverting the state and/or pulling the strings of global capital and/or devouring children and/or entrenching white supremacy.

There are only about 15 million Jews in the entire world — more people live in Guangzhou, China’s fourth most populous city. It’s a toss-up whether we’ve recovered in numbers from the Shoah, which killed two-thirds of all the Jews in Europe and about 40 percent of Jews overall. Majority populations tend to wildly overestimate the salience of minorities. When you understand antisemitism as, in part, a conspiracy theory about Jewish power, the virulence of feeling against us comes a little more into focus.

Mostly, I think majority-culture individuals just tend not to know who or what we are. The term “Judeo-Christian” has done so much damage on this front, roping us into a power structure built for our supersessionist oppressors. In open online communities, Jewish fans of The Untamed did what transformative fans do and sought themselves in the show — in the scholarly, rules-obsessed Lan sect, in the beleaguered doctors of the Dafan Wen clan, in the rebuilding of families wiped out on purpose, in the humor–as–survival strategy of protagonist Wei Wuxian. Somehow, a small, noxious group of non-Jewish fans found this deeply offensive.

The particulars were shockingly ugly, every time, and I won’t relitigate them. Mostly, these hurricane-force shitshows made no sense to me. With what power were our little stories threatening the span and splendor of Chinese culture and history? There’s a Parsi legend about Zoroastrian refugees who sail to India; they’re met on the shore by the Hindu king, who intends to turn them back. A language barrier prevents him from refusing them directly, so he pours milk up to the rim of a vessel: his kingdom is full and cannot accept any strangers. The quick-witted Parsi leader stirs sugar into the milk — there is room, he’s saying, and we will make your kingdom sweeter.

For just over three years, I was happy to be a guest and invisible in this particular online niche. Friendships crossed over into physical space; hotpot rewired my brain to crave it literally always; my lookbook of future husbands grew and grew and grew. All of it was such a balm against the outside world, even recognizing that media from anywhere will come with biases and problems. My Chinese and Korean shows were load-bearing: guaranteed happiness, pitted against the stresses of the day and winning.

What were you up to on October 7, 2023? It was the deadliest single day for Jews since the Holocaust: 1,200 murdered in every imaginable manner, sexual violence that shatters comprehension, 251 kidnapped to tunnels and private homes in Gaza. The horrors inflicted on the leftiest, most peace-seeking Israelis of all — the kibbutzniks, the partygoers at the Nova music festival — will shake you for the rest of your life.

I had to go to my banjo class at 11. “I have family over there,” I said uneasily to another dog owner that morning. He grimaced, with true sympathy, and he didn’t say anything awful.

הִנֵּֽנִי

One of the most Jewish things about The Untamed is how Wei Wuxian longs for nothing more than family and home, each of which are stolen from him over and over again. He survives under terrible circumstances, and that suffering doesn’t always redeem him. My beloved community of horny, curious, hilarious, thoughtful weirdos became inhospitable, anaerobic. “DEATH TO EMPIRE,” roared one acquaintance; another told followers to read a book about how Israelis harvest Palestinian organs. Emojis mushroomed in Twitter display names: the flags and watermelons are unobjectionable, the parachutes and inverted red triangles are an automatic block.

A few people reached out privately to express sorrow and ask if I was okay; they are more beloved to me now. Many were silent. Others could only see a Jew, the suspect kind, best excised. Disappointing: I may concede to being a ghost, but I reject that I’m a monster.

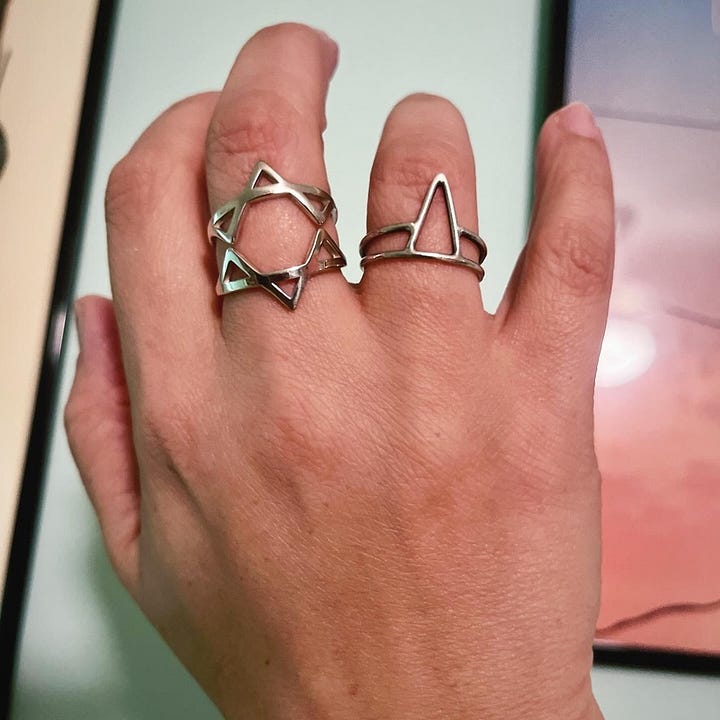

The thing is, I want to be seen as a Jew, as everything I love about my identity. I want hateful rhetoric and self-poisoning ideas not to survive contact with a flesh-and-blood Hebrew. There’s an internet-famous comic, in which a sailor asks a siren to sing something he likes more. She narrows her eyes and responds, “I will fucking increase the fucking thing.” Last fall, I desperately needed my own Magen David to wear; Instagram brought me to Arik Weiss, and I would fill my apartment with his art if I could. (When I got in touch to ask about sizing, I didn’t hear back for a few weeks and worried that something had happened to him. He apologized eventually: he’d been on reserve duty nonstop since the 7th.)

Last week, I was going to write about the Goryeo dynasty in film, but then six hostages were found executed in a tunnel in Rafah, the entrance a child’s room painted with Disney characters, and yoga teacher Carmel Gat was my age, and tall Eden Yerushalmi weighed 79 pounds, and Rachel Goldberg-Polin looks just enough like my mother, whose yahrzeit it just was, and 11 months of non-redemptive suffering collapsed into her eulogy for Hersh: finally, my sweet boy, finally, finally, finally, finally, you are free.

You’ve met the still, small quiet once you’ve sobbed yourself dry. Sometimes my brain, grasping for stimuli, fills it to the brim with music. Israel’s entry for Eurovision this year has earwormed me for months. The original submission was called “October Rain,” but that was deemed “too political,” so it was reworked into “Hurricane.” The creative team gave little or no ground. Both the music video and the live performances are unmistakably about the pogrom at the Nova Music Festival: singer Eden Golan recreating portraits of hostages and murder victims, the numeral seven hidden in plain sight on her dress, the circle representing a tunnel, the lyrics themselves. The Israelis were subjected to openly hostile competitors, throngs of protesters, heckling crowds and credible death threats, and they made the world face them anyway.

I want us able to talk about ourselves and each other. I want the art and the respect of being seen for everyone. We make; we witness. I want us all radiant, at our most alive. ✶

Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Eight Things You Can Do to Help”

Voice of America, “Far From Xinjiang, Uyghurs Keep Their Culture Alive”

The Tibet Fund, “How to Help”

The Center for Peace Communications, “Whispered in Gaza”

Daniel Bral, “The Best Hope for Peace Is the Israeli Left. Don’t Abandon Them.”

If you’re neither Chinese nor Korean, how do you relate to these media? Let me know in the comments or on Bluesky. I love recs and growing my teetering to-watch list.

Thanks for reading Excited Mark! If you’d like to support my work, please share, toss a few bucks at my Ko-Fi or become a subscriber, free or paid. I’m also available for hire as a fact-checker, editor and journalist — visit my RealName.com for clips, services and more.

Spring Thoughts Under Moonlight: Getting It On in Fantasy Ancient China

Selling out is another one of those universal dilemmas. Is it better to make the story, even in an altered or watered-down form, so it might open more people to the original? Is it worth it to change something important to your story to placate a censorious state and a socially conservative widest-possible audience?

I was in an Uber yesterday with my 9-year-old, who has a Hebrew-sounding name. And our driver was a man named Waleed whose profile says that he speaks English and Arabic. And for just a second, I had this notion that I should probably tuck my Magen David into my shirt. I didn't. But the fact is that we need courage to be Jews in the world in 2024 in America is... something.