Fashion in Historical Kdramas: The Sageuk Silhouette

Clothes maketh the character, and hanbok has a lot to teach us about Korean history.

In the autumn of 2016, a friend hooked me up with a part-time job at a boutique in New York, the kind that sold clothes by one designer. Because we offered tailoring services with our outfits, I learned the most basic baby steps of alteration work. That’s how I got to meet Lea DiLaria (super nice, chilling with friends), Amy Sherman-Palladino (just needed a quick gift, no unnecessary chatting) and Amber Gray (so nice, but definitely told me she was an opera singer when I had just seen her in Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812).

In addition to pinning hems and lifting shoulders, we had to identify every customer’s basic body shape (without bringing it up) so we could suggest different pieces. I was an hourglass, but we also slotted people into apple, pear, inverted triangle or stick. This was a lesson from drawing that I’ve never fully nailed down, the ability to break down an object into its simplest parts. Even I, however, took one look at the costumes in my first Korean historical shows and went, Wow, that’s a triangle — I wonder why?

One thing I love about sageuks, the period kdramas set more or less before the 20th century, is that because they’re anchored in history, the worlds they build can feel so brand-new to me and also so complete. If the production team is meticulous, the past can come alive; if everybody’s just having fun, anybody can get the jokes.

Learning the visual language of hanbok and other historical clothing, however, was a steep learning curve. How many layers is that? What is everything called? Why are there so many hats? Is everyone at the palace really just walking around in socks? And of course, the big one: Do I understand why the characters swoon for these fits?

What is the what

My baseline expectations for fashion were forged by late-‘90s issues of Seventeen and an earnest attempt in my 20s at a pin-up phase. Ideally, I believed, clothes should complement or accentuate your body shape by revealing or fitting to it while expressing a subcultural aesthetic. This is not the philosophy undergirding hanbok, which emerged by the first century BCE and has continuously evolved (though not too much) through two millennia.

The word hanbok only emerged to describe Korean traditional clothing in response to colonialism, particularly 20th-century Japanese colonialism, which brought with it an embrace of Western-style presentation. Before they needed to be explicitly Korean, clothes were just clothes. Hanbok is also a South Korean term; in North Korea, these garments are called chosŏn-ot (“Joseon clothes”).1

Hanbok is egalitarian in form, if not in material. It’s designed to accommodate, rather than call attention to, every body type. “Its fundamental structure can be stitched from three basic parts,” writes Ki Lee of online shop The Korean in Me. “The first is the jeogori, which is the basic upper garment of the hanbok or what most usually refer to as the ‘short jacket.’ It is worn with a chima or the skirt for women, or a baji or pants for men.” Depending on how much social status you want to show off, you may layer on an almost impossible number of garments; see below for what’s expected of a noblewoman about to marry the king.

A lot of theory goes into constructing hanbok. The crisp lines at the neck coexist with the voluminous curves of the woman’s chima, which creates the impression that she floats as she walks. The arc on her sleeves also mimics the shape of traditional tile roofs, connecting the wearer to her setting. Decorative elements on the fabric for all wearers often emphasize nature and thus connection to the land, while formally, the graceful motion of the cloth calls to mind the elegant flow of water.

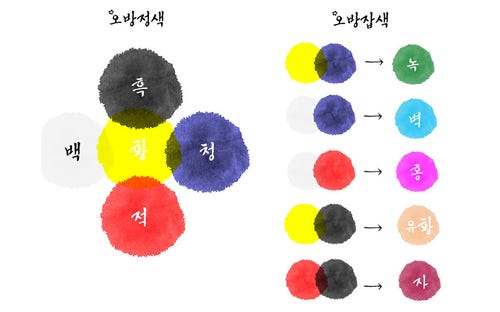

Furthermore, designers of everything from clothing to food to buildings to rituals rely on a color theory called obaengsaek, derived from “the yin and yang elements: white (metal), red (fire), blue (wood), black (water) and yellow (earth).” Each color and combination thereof carries a rich symbolism rooted in wishes for the wearer, expressions of status and proclamations of character.

Material world

Clothes everywhere serve many purposes, from shielding us from the elements to identifying us with an in-group. Hanbok is especially visually rich for designating a person’s place in society. How you wear your hair announces whether you’re married or not; different professions have strikingly different uniforms, whether you’re a painter, a laborer with specialized skills, a merchant, a physician or a kisaeng, educated female entertainers. Noble and/or wealthy people dress in silk, gauze, satin and damask, while common people rely on cotton, ramie and hemp. In dramas, you’ll often see poorer characters wearing straw shoes; they’re called jipsin, and they’re meant to be replaced quickly and cheaply.

Something that makes sageuk costumes so ravishing, of course, is the attention to detail. I love the stunning embroidery on an official’s robe, which tells us his rank in government, or the elaborate binyeo hair ornaments that somehow always reflect a character’s temperament. Perhaps the most fun, however, is the hats. There are simply so many kinds of hats!

All this serves to create order in society, specifically that determined by Korean Neo-Confucianism. To explain this, I’m relying on a few different sources, including an excellent thesis by Eunji Choi on cosmetic surgery. Very broadly:

Neo-Confucianism emerged as a reaction to Buddhism especially, which was dominant in the Goryeo dynasty but came to be considered too unmoored from the real world. When the Joseon dynasty overthrew the Goryeo era, it established its own philosophical scaffolding in the kingdom.

Crucially, human nature is inherently good.

Integration of individuals within wider wholes scales. For instance, the body and mind are considered one, as are members of a family (past, present and future), as are members of a nation, as is a nation with the land and the universe.

This is why everyone in sageuks has long hair — your body is a gift from your parents, and leaving it unaltered demonstrates filial piety.

Reverence for social and universal order creates and sustains harmony, which is the natural state of the world.

Society is hierarchical because everyone plays their part to maintain social order. Men and women have reciprocal social roles that often do not overlap.

However, some mobility is available through education and self-improvement.

Of course, storytelling is almost always about people who don’t fit in, who push boundaries, who want too much, who live their own lives. These social structures create all kinds of opportunities for beloved misfits — especially cross-dressers, from scholars to kisaengs to the king herself.

Hanbok and Hallyu

Sageuks and the Korean Wave overall (kpop, kdramas, skincare, &c &c &c) have created space worldwide for an interest in hanbok. Beyond dramas, there are whole communities of artists and fashionistas who are transforming hanbok at home and abroad; look up “modern hanbok” on Instagram for a taste.

“‘Traditional’ clothes, in popular understandings, seek to quaintly emphasize national and cultural uniqueness, the longevity of traditions, the power of hierarchical structures and the women-wearers’ own demure acceptance of the same,” writes Dr. Srijana Mitra Das, who continues: “An especially intriguing notion is that ‘traditional clothing’ in Asia may now represent the agency and power of the Asian woman to creatively fashion her own image and aspirations … while negotiating the many mazes of identity, possibility, limitation and mockery that complex historical, social and political phenomena have led her towards.”

Kim Young-jin is one such designer. Her label Tchai Kim takes the form of hanbok seriously while using materials from the world over as inspiration. “To create something new out of tradition is a search for self,” she says in one interview. I love how she uses fashion to investigate history, gender and the pandemic in the video below:

I couldn’t fit every resource and recommendation into this piece, but if you enjoy hanbok or are hanbok-curious, I highly encourage you to spend some time with the following:

This making-of video shows off how tailors and artisans assemble and decorate hanbok, including how they gild silver or gold patterns on the sleeves of royalty.

Fashion in the Goryeo era differs from that in the Joseon era; here, one blogger looks at the costumes in two Goryeo-set series and explains their Chinese, Mongolian and indigenous influences; here, another goes deep with more shows and a wider reach. Meanwhile, Glimja’s Hanbok Story combines meticulous historical research with vivid yet darling illustrations to explore the evolution of hanbok from our earliest records onward.

The New York Times used the release of the 2022 series Pachinko to explore what hanbok has meant to immigrant families in the Korean diaspora (gift link).

Hanbok Heroes contains original research and documentary photos from Ying Bonny Cai, a Fulbright scholar and designer investigating modern and historical hanbok. Everything she presents is gorgeous and informative, so go see for yourself what she’s found on the street and in the archives.

Finally, for some absolute swagger, watch these hot Brits absolutely slay the first London Hanbok Walk. ✶

What are your favorite costume dramas? Let me know in the comments or on Bluesky. I love recs and growing my teetering to-watch list.

Important boilerplate for the people

Thanks for reading Excited Mark! If you’d like to support my work, please share, toss a few bucks at my Ko-Fi or become a paid subscriber. I’m also available for hire as a fact-checker, editor and journalist — visit my RealName.com for clips, services and more. Most appreciated!

For an accessible scholarly article on hanbok as a means of asserting national identity, I recommend “Fashioning Modernity: Changing Meanings of Clothing in Colonial Korea” by Dr. Hyung-gu Lynn; you can read up 100 articles on JSTOR free per month with just an email address. To see that clash in action, watch the 2018 drama Mr. Sunshine on Netflix, although be prepared — it is A Lot. Yes, it’s the one with Teddy Roosevelt as a speaking role.