Kdramas and the Bureaucracy of the Afterlife

Grim reapers, reincarnation and performance reviews with the Jade Emperor: Korean TV has a lot of questions about work in the hereafter.

Heads up: The shows discussed this week deal extensively with suicide, though it is not mentioned in this essay. Please take good care of yourself. ✶

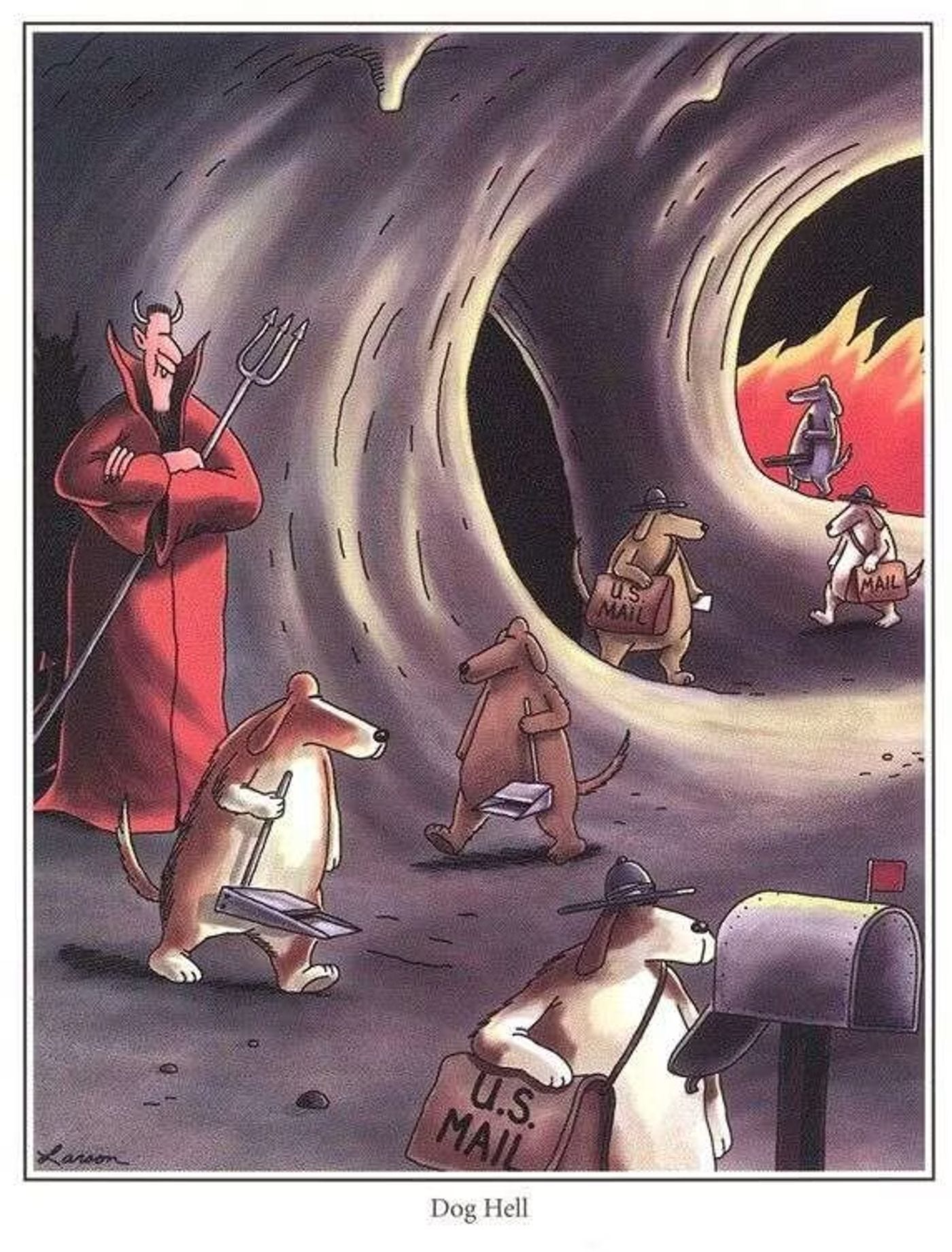

During the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, I grew up with the local alt-weekly and the cultural artifacts of three much older siblings in my house, which means one of my foundational texts is Gary Larson’s The Far Side. Learning to read on his one-panel absurdist genius had a lasting effect on my personality. Since I am Jewish and didn’t learn much about the afterlife one way or the other as a kid, The Far Side was also probably my first exposure to concepts like Heaven and Hell.

It’s hard not to spin up comic conceits of Hell as a workplace — certainly films like Office Space cement that impression in Anglophone pop culture. To work even after you die, to be tied to your desk and your horrible boss for eternity, represents the ultimate loss of agency. Death is supposed to be about rest and respite, if you’ve been decent in your life. To have a job in the hereafter can only be punishment alone.

The first Korean grim reaper I met was Lee Dong-wook, nameless for most of Goblin (also called Guardian: The Lonely and Great God). I think of him as “sexy Eeyore” — though he is handsome, Reaper is not good at being a person. He and his housemate, the 900-year-old dokkaebi Kim Shin, fight and annoy each other like brothers, while the woman he loves has trouble extracting the simplest facts about him. (This is not fully Reaper’s fault; not only must he keep his present identity secret, he also has no memory of who he was in life.)

In his work, however, Reaper is diligent. Each day, he’s given a number of cards with the names of those who will die. He collects souls and brings them to a private room, surrounded by thousands of handmade teacups. He explains what will happen next, and he sends most of them off with a special tea that erases their memories and allows them to reincarnate fresh. Sometimes he deals with irritating paperwork; sometimes he attends mandatory-fun team dinners. He works a shift and then he goes home, where he has a life outside of work. He has been doing this for hundreds of years.

Every grim reaper in Goblin has been wiped clean of their past, although they understand that in that past, they committed some great sin and this is their atonement (though not punishment) — an eternal present, and work.

Nice work if you can get it

Goblin marked a cultural reset, but it wasn’t the first of its kind. Many fans and scholars point to 2013’s My Love from the Star as the kickoff for the paranormal urban fantasy romance trend in kdramas; I haven’t seen it yet, but it seems to involve an ageless alien who’s stuck on Earth long enough to witness cycles of reincarnation. In fact, there are lots of dramas about uncanny functionaries throughout East Asia, including in China, where portraying reincarnation is a high-wire act if it’s not about celestial immortals going through tribulations in the Mortal World.

Much more common is the office comedy, exemplified by the satirical Gaus Electronics, or simply the office as a major backdrop in any modern plot. This makes sense in a country that nearly saw an officially sanctioned 69-hour workweek.1 “On average, South Koreans work 1,915 hours per year, the fifth highest among countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development,” wrote NBC’s Josh Lederman in 2023. “By comparison, Americans work an average of 1,791 hours annually, while the average is 1,490 hours in France and 1,349 hours in Germany, according to OECD data.”

Younger Koreans face many of the same social and economic pressures that have led their same-aged cohort in China to embrace “lying flat,” a throwing up of hands at a hypercompetitive work culture which barely rewards them and discards them at will. Unstable finances among young people in South Korea keep the MZ generation from marrying, moving out of their parents’ households and establishing careers that keep them out of poverty as they age. “Jobs with good prospects and decent salaries, such as full-time positions at large companies with more than 300 employees, account for only about 10 percent of all jobs in the country,” one professor told The Korea Herald last fall.

In Tomorrow, we meet Choi Jun-woong (Rowoon) interviewing for a position at a fertilizer corporation. He brightly delivers an over-the-top pitch, comparing himself to nitrogen, which is “useless” on its own but can encourage life for plants when converted into ammonia. Despite the hiring committee’s delight at his metaphor, as soon as he leaves the interview, Jun-woong receives a text saying he’s been passed over — the milquetoast other finalist, it turns out, was a member of the company owners’ family.

Later that evening, Jun-woong gets caught up in an accident and, thanks to an act of heroism, falls into a coma. In recognition of their error, the grim reapers of Jumadeung2 offer him six months of work as a reaper himself, so he can wake up from his coma early. One of the deal’s selling points is that he’ll get the job of his choice among the living once his contract is up. Jun-woong cannot find work, in other words, until he’s effectively died.

A civil service for the ages

Tomorrow shows us most explicitly a vision of afterlife workers as members of a corporate hierarchy. Different teams take on different portions of the death process, from creating life-montage videos to executing contracts on standard terms for concluding a life. They use phone apps and tablets to monitor problems and coordinate projects. Yet even with the trappings of a recognizably modern Korean workplace, they don’t react to their work like characters in a workplace show. That’s because it’s the wrong model — kdrama grim reapers aren’t modern office drones or even a drama-friendly occupation with a higher purpose, like physicians. They’re Confucian bureaucrats.

Interestingly, Korea’s jeoseung-saja (literally “afterlife messenger”) have always been civil servants. The black hat is a crucial part of their uniform; in Goblin, the horsehair gat is recast as a “vulgar” fedora. The jeoseung-saja cannot be deterred, but families can leave offerings on behalf of the dead as a bribe, in hopes that the jeoseung-saja will advocate for their dead before the judges of the underworld. To earn a place at Tomorrow’s Jumadeung, would-be reapers must pass an exam requiring years of study. Only the most elite can join the Escort team, which collects souls and leads them to the Hwangcheon Road and what’s next. Even the workplace of Tale of the Nine-Tailed’s psychopomps is styled as the Afterlife Immigration Office.

Korean Neo-Confucianism played a foundational role in governance and administration during the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897). It’s an intensely hierarchical outlook, in which the king “is crucial in binding the people to the land and to heaven,” as Incheon University’s Chad Anderson puts it. “This kingly role is natural. The Confucian order is not designed by man. Thus, the entire order of the world, society and the environment [is] linked and natural. They are not a contractual order like the order of government under the rule of law.” The kings of Joseon were both balanced and served by a bureaucracy, which University of Washington Koreanist James Palais defines as “functionaries recruited by impersonal standards of merit, talent or achievement.” This leads to a “ruling class as an elite of virtue.”

In this light, organizing the afterlife so that grim reapers are crucial to the workings of the universe makes sense. Even wiping the Goblin grim reapers of their memories allows them to be agents, nothing more or less, unburdened by a past life that could interfere with their service. We don’t really see the king, as it were, in kdramas,3 but we get to know their direct reports. “The ideal government is to study and apply Confucian principles in practice and as an example to the people,” Anderson writes. “The more the king and his people do this, the better they link heaven and earth, bringing prosperity to the people.”

That’s the scholarly ideal, of course. Politics and power struggles defined the traditional yangban class, and in Tomorrow, the emotional climax rides alongside a board vote for the King of Hell to unseat the Jade Emperor. Afterlife bureaucracies aren’t your average office dramas, much as I love those. Pour one out for the jeoseung-saja who make them run. I sob myself dehydrated during every episode of Tomorrow, and our Grim Reaper in Goblin is simply one of my favorite characters of all time. The genre play in these stories asks universal questions about the ultimate in transcendence and the ultimate in mundanity. The workers may be anonymous, but at the moment it counts, they’re everything. ✶

Have I missed your favorite grim reaper? Let me know in the comments or on Bluesky. I love recs and growing my teetering to-watch list.

Important boilerplate for the people

Thanks for reading Excited Mark! If you’d like to support my work, please share, toss a few bucks at my Ko-Fi or become a paid subscriber. I’m also available for hire as a fact-checker, editor and journalist — visit my RealName.com for clips, services and more. Most appreciated!

From Vice: “Perhaps counterintuitively, the proposal was meant to help solve the fertility crisis currently plaguing South Korea, which has the world’s lowest birth rate. Allowing workers to accumulate more overtime hours in exchange for time off later could give people longer breaks to start or care for families, the government said.”

This has been translated as “phantasmagoria,” but it refers to the flickering of a zoetrope and is more directly related to seeing your life pass before your eyes before death.

Your writing is top-notch! Love all these deep dives into a subject wholly unfamiliar to me.

How does Hotel Del Luna fit in all this? Definitely not a bureaucracy, Confucian or otherwise—though that snazzy purple wide-brimmed extravaganza makes for an eye-catching replacement for the gat!