Why We Love to Finish Bad Shows

This isn't about hate-watching. It isn't even about appreciating buried potential. This is about scratching a primal and unvoiced itch.

My mom had an amazing gingerbread recipe — not for cookies, for deep pans of moist, rich, complex spice cake. When I was first venturing into the world, I tried on several occasions to recreate this feat to impress people. During the first attempt, in college, I was literally working at a campus coffee shop; there was also a Starbucks around the corner from our apartment. A boy was in the kitchen with me, and I was trying to look smart and cool. I didn’t have liquid coffee (I am a tea drinker, coffee is too strong for me), but one of my roommates kept a jar of instant coffee crystals.

I did not use those to make coffee; I added the crystals straight for some reason. We later calculated that because of its concentration, the infinitely dense loaf I created held 190 times the amount of coffee needed to satisfy the dish. Another time, at my first office job, where I was a temp and so badly wanted to be hired permanently, half the batter somehow ended up on my ceiling and also I entirely forgot to add ginger. My mother kept asking me, kidding but not really, not to tell people it was her recipe.

I am sympathetic to grand failures. I also later achieved the gingerbread. And of course, it’s a great story now. When a story is bad somehow, though, the investment is not shopping for ingredients but time. In our one wild and precious lives, do we have time for terrible TV?

Yes. Yes. Oh my god, yes.

I have inhaled nonsense that would bring connoisseurs to their knees. I just finished one kdrama about a 1,500-year-old ghost who possesses a particularly dim idol to get revenge on the reincarnation of his lover, who is a firefighter. I’ve seen productions simply run out of money and handwave the ascension of the female lead into another universe. I’ve seen spinoffs perform total personality transplants on endearing side characters turned leads. There’s a series about a family whose members, for generations, turn into a dog upon their first kiss; in another, a CEO’s childhood gene therapy was sabotaged by a business rival to give him uncontrollable husky traits.

Describing a show as “bad” owes something to Justice Potter Stewart’s definition of pornography: we know it when we see it. I wouldn’t call Word of Honor a bad show, but I wandered off after 13 episodes and don’t care to finish. Moreover, there are simply so many ways a production can be bad, and these hit different for every viewer. Ms. Cupid in Love is not high literature, but I have watched it twice and would happily introduce it to any friend. “Bad” is not always a value judgment in TV, and teasing out what makes me stick with a bad drama helps me decipher my taste, my id and the holes in my education.

A case study in mark-missing

The Scholar Who Walks the Night has one of the highest great-title-to-terrible-show ratios of all time. When it came out in 2015, we were years into a vampire renaissance. In the U.S. alone: True Blood, The Vampire Diaries, Twilight, freaking Buffy the Vampire Slayer — we were saturated. Sweden and Iran were winning international awards with vampire films. We had so much lore to choose from, so much to study and remix. In South Korea, 2013’s mega-hit My Love from the Star had opened the floodgates for fantasy-inflected dramas. Dropping vampires into a sageuk was basically printing money, and Scholar had already proven itself as a successful webtoon.

Here is the story engine this show presents us:

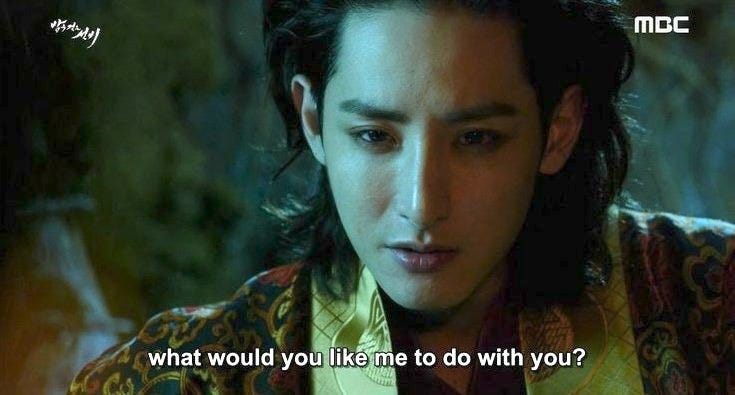

Gwi — A centuries-old vampire who lives beneath the palace, acts as a shadow power behind the throne and eats the occasional concubine as payment

Kim Sung-yeol — A “good” vampire who was turned against his will in order to protect the royal family from Gwi

Jo Yang-seon — A spunky cross-dressing bookseller with a mysterious past whose blood smells extra-amazing to all vampires

It’s the thesis of both Hadestown and Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others that we keep coming back to stories we know in the hope of seeing something new in the familiar. The stock characters that populate Scholar are an opportunity for a naive viewer like me to better absorb what’s novel. The supporting cast promises even more riches: I was particularly taken by the brilliant, lovesick kisaeng whom Kim Sung-yeol refuses to turn, and the heartless crown princess whom Gwi earnestly loves.

I don’t know how it went so entirely off the rails. Here is some of what I wrote on first contact with the show:

I regret to announce that Scholar is, with a few exceptions, almost entirely devoid of artistic merit, technical achievement, creative daring or storytelling instinct. I have circled around from rage at how shockingly, stunningly, egregiously and aggressively bad it is to full ensorcellment.

[Most of the cast] seem to be acting in a community theater production — with no chemistry, spontaneity, relatability, charisma, personal appeal or intelligence.

Imagine you’re making a period piece and a vampire show and you don’t take advantage of literally any stylization or genre cues. Everything is flat and bright and straightforward. There’s very little depth of field or color contrast. There’s no cinematography to speak of. There’s no pacing! The editing is bewildering! The episodes just peter out mid-shot!

When I railed about the musical choices (“strange modern ballads to tell you what to feel, sure, but also... this, like... silent movie–era/polka????/jangly-intrusive score???”), one friend bravely suggested it was an homage to Nosferatu. There is certainly some pre-talkies overacting from the lead, but mostly he has scared me off any of his other projects, even the ones that sound super interesting.

And yet… and yet.

The second time I watched Scholar, I fast-forwarded through the chaff. Yes — I watched it a second time! There are fascinating stories hidden in the muddle and missed opportunities, and they might feed my own projects going forward. Jo Yang-seon is caught out in her disguise — how does she relate to living as a woman by fiat? One tertiary character is turned into a vampire — what role could he play once he’s through the mindless fledgling stage? The crown princess is trapped between her power-hungry father and Gwi — how does she choose to survive? And of course, there’s our villain: gorgeous, lonely, disdainful, inhuman, vicious, horrible, magnetic Gwi.

Most of the time, we get too much backstory in dramas, and there is something refreshing about Scholar’s insistence that Gwi is simply a parasite who showed up one day and overthrew a dynasty to guarantee a lifetime supply of human blood. He’s grandiose and deeply unhinged, and yet strangely reluctant to cash in on his power. At least five of the Chekhov’s guns that never go off in Scholar he keeps hoarded in his underground lair, including the mummified corpse of the king’s father (which we know vampire blood can resurrect as a vampire at any time after death!! sorry, I’m still mad). When “guardian vampire” Kim Sung-yeol confronts Gwi in the final battle, he deploys the only interesting observation he makes in the whole show: You’ve been here for centuries, and yet you never tried to live even once. You’ve just been dead this whole time.

As someone who is easily excited, I will not beat around the bush: Gwi actor Lee Soo-hyuk is one of my future husbands. At least one-third of the views on the short video above probably come from me sharing that knee-squeezing deep voice (and one life-changing grunt) at unsuspecting friends, acquaintances and strangers. I dredge up lots of bad shows in a favorite actor’s filmography, and I’ve always been fascinated by dues-paying projects; I wonder so much about the experience and context of making them. Scholar isn’t even the first time Lee Soo-hyuk has played a bloodsucker opposite lead actress Lee Yu-bi — you’d better believe I’ve watched all of Vampire Idol, in which a quartet of vampire aliens get stranded on Earth and become kpop trainees.

There’s plenty of value in dissecting a bad show to understand where it went wrong for you, as well as in figuring out how you’d fix or explore it. The more I looked at The Scholar Who Walks the Night, the more I wondered about the Watsonian versus Doylist sources of these issues — what was a production issue, what bothered me about a performance or narrative choice, what was a genre convention I didn’t yet understand. Not everyone approaches other people’s stories with a transformative lens, though, and I think only validating stripping a show for parts doesn’t allow us the full freedom that loving bad TV can offer.

Life’s too short to play it cool

Coming up with pithy, technically correct summaries of the shows I’m watching is one of my constant pleasures in life. It’s such a delight to pitch more and more deranged plots to disbelieving querists. Yes, the series about preferring your robot boyfriend rules, actually! Yes, the drama about the modern guy who wakes up in the past and attempts to get rich by inventing modern conveniences is great — yes, and the other one is too.

Often during our calls, one friend will ask if I’ve seen something and then interrupt himself: No, what am I talking about? You don’t watch shows in English.1 It is my sense that large swaths of Anglophone mass media are cowardly these days. That staleness is not simply a matter of relying on proven IP: many kdramas and cdramas are adapted from self-published webnovels, online comics and shows first made in other countries. They work even in the face of multilayered censorship, imposed by both state and self.

I think profit motives and people-pleasing degrade a story more than almost anything (though you can’t pretend these don’t also infuse c-ent and kdramas). I think the satisfaction of amateur storytelling — fandom, done for the love of it, for a precise niche audience — partially proves this point. My basic thesis of fiction is that we will wade through nearly any amount of dross if we care about the characters. I learned this from improv, in which I took classes as mandated when you live in Chicago in your 20s. A good improviser can accomplish anything with a clear understanding of who they are and what they want in that moment. The audience wants to ask questions about what they take in, to also participate by being present and immersed.

The true mark of a bad show that you finish, to me, is that it feels like play, not only in that it’s fun and fearless, but that you’re full-body invested. Something about this narrative is speaking to your true, deep, unembarrassed self. You’re fascinated. You’re free! If you’re not moved to put more time into a story, don’t bother. But it’s neat to know what you like and be unabashed; it’s good practice. I’ll seek that out wherever it lives — transformation, homecomings, moments of truth, monsters, identity trouble, craving connection over power.

Hey: I just told you a lot about myself. ✶

What’s your favorite bad show, in any language? Let me know in the comments or on Bluesky. I love recs and growing my teetering to-watch list.

Thanks for reading Excited Mark! If you’d like to support my work, please share, toss a few bucks at my Ko-Fi or become a subscriber, free or paid. I’m also available for hire as a fact-checker, editor and journalist — visit my RealName.com for clips, services and more.

Aesthetic Violence and Why We Love It

My experience with self-defense or martial arts is limited to one lunchtime workshop several jobs ago, but when I’m immersed in a great fight onscreen, I feel like I can take credit for it after.

This is not entirely true! I am currently enthralled by a late-Aughts History Channel docuseries called MonsterQuest. Nothing beats earnest-but-skeptical-but-open-minded cryptid investigations. Can I interest you in the truth about rods?

I’m sure your mom would be relieved to learn that I absolutely never remember that the gingerbread coffee calamity was an attempt at her recipe. 😆

Absolute fave bad show: Bridal Mask! That thing is a wreck! It has the literal worst wig I’ve ever seen in any show or movie, all countries combined! The main character is a violent asshole who’s only happy to bow down to his new Japanese overlords!

And yet!

Can’t get enough of that crack!