Why the Hero Is Coughing Up Blood

Acupuncture, qi, vital points and foods with energy are all part of how traditional Chinese medicine takes care of the body — and the narrative.

One of my favorite people in Brooklyn was my massage guy. I chose him because his Yelp reviews mentioned he used to be a construction foreman. My biggest treat to myself was a monthly hour in his care, which I had to give up when COVID hit. At that point, six years in New York was more than enough for me, and on Halloween 2020, I drove my dog and my most breakable/important household items to Chicago, where I was still isolating but at least much happier with my surroundings.

I did miss that bodywork, though — only my canoe-obsessed, nerdy-hilarious massage guy was now a whole time zone away. It was winter and I didn’t want to go that far; all that was in walking distance was an acupuncture clinic. I wasn’t afraid of needles, but I was more than a little suspicious. Surely acupuncture belonged in the same category as essential oils and chiropractic. Then… okay, yes, then I watched this kdrama.

Live Up to Your Name! is a madcap mash-up of history, plot devices and modernity. The greatest acupuncturist of the Joseon era uncontrollably lurches between the 1590s and the present, sometimes in the company of a brilliant cardiothoracic surgeon who rejects Eastern medicine (and her father’s livelihood) entirely. It is deeply goofy and also quite compelling. The acupuncturist (real-life giant-of-the-field Heo Im) fixes all kinds of ailments with a well-placed needle, from bowel obstructions to psychiatric flare-ups to anesthesia. Surely that’s a dramatic device, I thought. Surely that’s not what happens!

My acupuncture lady is also hilarious, as is the fact that I have an acupuncture lady, whom I also see once a month. I could not tell you how it works, but anecdotally, something happens. One day at the gym, I pinched a nerve in my knee and was plunged into the weirdest, most unrelenting pain of my life. I couldn’t sleep at night, was too nauseated to eat and could barely move. The next morning, my acupuncture lady stuck three needles in my ear and from one moment to the next, it all relented.

Since watching Chinese dramas in particular, I have seen so many new-to-me bodily functions and baffling-at-first treatments. Sometimes characters get so emotional, they spit up blood. Endless side quests direct our protagonists to gather exotic or rare ingredients for a crucial concoction or for refining a pill in an ornate cauldron. Physicians can diagnose any condition just by taking a pulse. Martial artists know precise targets on the body to incapacitate an opponent. Love interests nag each other not to eat foods with metaphysical properties.

If something about this system didn’t work, I’d tell myself, the whole thing would have been discarded ages ago. I had no basis to evaluate most of it, however, as genre convention, medical practice or diasporic inheritance.

TCM for short

I love learning about science, but I am not a scientist. Narratives come easily to me, though, and traditional Chinese medicine presents a unified theory of the body that’s absolutely fascinating. Its concepts undergird depictions of bodies in both historical and fantasy dramas. One modern medical drama, starring headliner actress Zhao Lusi, explicitly sets out to demystify its practitioners in a relatable contemporary setting.

We begin, as we so often do, with Confucianism. “[A]ccording to Chinese tradition,” writes Sinologist John William Schiffeler, “the human body is a part of nature and functions in concert with the principles that constitute and regulate nature.” From that first principle, TCM derives and scales all further observations.

This post took longer than usual to draft in part because concise, accessible and non-corny material that explains TCM is not thick on the ground (thanks, enshittification). Though it’s not pseudoscience, there are an awful lot of grifters in the English-language space. With special thanks to the National Library of Medicine, if you know nothing else about TCM, you should know these two elements.

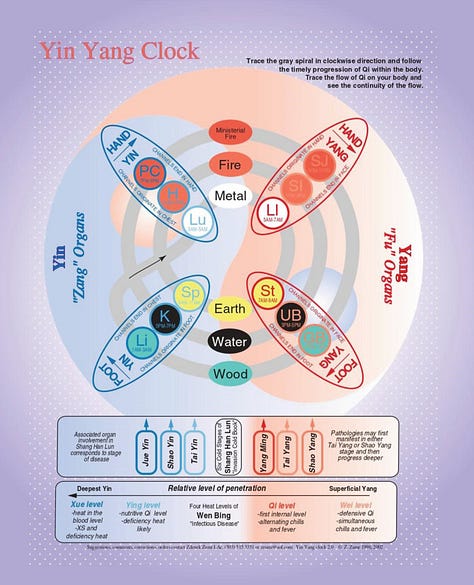

Yin and yang: You’ve likely seen the Taijitu, the monochromatic symbol (☯️) that I first encountered as a tween at Claire’s Accessories. Visually and philosophically, it exemplifies observable truths about the universe as “unity of opposites” and “balance among dynamic forces.” Imbalances in the body are corrected with treatments like acupuncture, diet and herbal pharmacology. To see the interplay of these forces at work, spend some time with Five Elements Theory (write-up | video).

Qi and meridians: The energy that makes you alive travels along certain pathways in the body. Not only can qi be deficient or excessive, it can also be blocked or stagnant, which informs treatment and maintenance.1 In xianxia, one of the worst things that can happen to a spirit cultivator is qi deviation (mirroring a real-world condition called zouhuorumo), which can shatter your meridians and is heart-rending onscreen.

Is there a doctor in the house?

I’ve just started Mysterious Lotus Casebook, which everyone was watching last summer and, I can say so far, for good reason. An overconfident probationary detective and a droll “miracle” physician with a wuxia RV solve crimes and (presumably) get to the bottom of a larger mystery, all while bickering and one-upping each other. Promotional materials suggest a terse antagonist will join them down the line for a real odd throuple vibe. I don’t have context yet for the above scene, but it does showcase a number of common fantasy/historical TCM moves in cdramas, including pulse diagnosis, detoxification and acupoint paralysis.

Doctors, apothecaries, pharmacists and all manner of healing professionals populate Chinese and Korean period TV. They may be a solemn or reassuring walk-on part or an integral role within the ensemble. Interestingly, one study found that while U.S. medical dramas are most concerned with positive representation of medical workers overall, Chinese and South Korean shows tend more toward depictions of corruption within healthcare systems. Many of my favorite onscreen physicians are brilliant if somewhat antisocial cranks, like the Lothario Pei Huai in The Sleuth of the Ming Dynasty or prickly peak eldest daughter Wen Qing in The Untamed.

Yet expectations for proper behavior and medical ethics among doctors were recorded as far back as the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE). Medicine was called “the craft of saints” in The Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Internal Medicine, possibly the oldest medical text preserved today. Furthermore, writes political scientist Guo Zhaojiang, “all patients are equal before a physician. This concept was significant and progressive in a hierarchical, feudal society.”

“The Confucian concept of ‘justice before benefit’ requires doctors to give justice priority and to regard honesty as a duty,” Guo continues. “Confucius outlined a series of principles and norms for showing respect for and sympathy to people, based on an appreciation of human values and human dignity.” The radical universalism of the human body was especially noteworthy when physicians, who often occupied a fluid position below royalty but above skilled artisans, treated the ruler — illustrating “the tension between the body as an anatomical or clinical subject and the index of social hierarchy,” as pop culture scholar Liew Kai Khiun observes.

Generative vs. Institutionalized

Some of the theory that organizes hanbok and other Korean costume traditions also informs Confucian approaches to the body. In his paper on medicine as portrayed in sageuks, Liew tackles an interesting conundrum: as one’s body is a gift from one’s family and should not be altered even to cut the hair, how can a Confucian physician use surgery or other alterations to rescue a body in need?

The solution lies not in discarding Confucianism but reframing it in its own yin-yang modality. “Just as the intrinsic goodness of human nature needs further moral cultivation and refinement to reach its full potential,” Liew writes, “the human body can be cultivated according to Confucian bioethical traditions.” The physician does not impose a “sense of justice” but instead “actively [assists] nature.” He identifies a trap to avoid:

As part of ‘Generative Confucianism,’ the physician provides a more dynamic [yang] and adaptive application of ancient Chinese philosophy by developing, incorporating, universalizing and archiving new medical practices. In contrast, the passive [yin] … ‘Institutionalized Confucianism’ is the obstinate adherence to dated modes of healing and medicine even in the face of crisis.”

This mirrors “[t]he intent of acupuncture,” as Medical University of South Carolina’s Gary Nestler describes it: “to stimulate the body, releasing energy blockages and re-establishing the body’s equilibrium. Through this process, the body’s natural ability to heal itself is stimulated.” And narratively, Liew argues, low-born kdrama court physicians “are the protagonists precisely because they are willing to engage directly with the human body as a corporeal rather than symbolic subject.”

One nonfiction book I’ve enjoyed recently is The Genesis Quest by Michael Marshall. It’s a history of the search for the origin of life, cogently and often wryly underscoring how we still don’t fully know how and why life happened. So much of it, from billions of years back to the present, is about keeping the primordial ocean close to us, which is accomplished by building a boundary — a cell wall. What maintains that system is homeostasis, the feedback loops that ensure balance inside the body and its functions.

Allopathic medicine and TCM have been in deep conversation for several decades now. I haven’t put in the time or the work to be able opine on the science. Now, though, I can better appreciate the scaffolding on the stories I enjoy. There’s a reason it’s stuck around in people’s lives for so long. ✶

Who is your favorite c-ent or kdrama physician? Let me know in the comments or on Bluesky. I love recs and growing my teetering to-watch list.

Four or Five Strings: Musicians in Korean and Chinese TV

The oldest playable instruments in the world are 9,000-year-old crane-bone flutes found in Henan. (You can listen to them here!)

If music reflects the true nature of the world, in action, it may be a primal force in the universe.

Thanks for reading Excited Mark! If you’d like to support my work, please share, toss a few bucks at my Ko-Fi or become a paid subscriber. I’m also available for hire as a fact-checker, editor and journalist — visit my RealName.com for clips, services and more. Most appreciated!

This also applies to substances within the body, including blood. Unless the character onscreen has been wounded, it’s generally a good thing when they cough up blood — they’ve expelled an obstruction of some sort.