Don't Think Too Much About Product Placement!

Art and commerce are always in tension, but big picture, we may have lost the plot a little.

A king from a parallel universe arrives in the Republic of Korea on horseback — a phenomenal fish-out-of-water tale already! The horse is white, and named Maximus; the king is Lee Gon, a handsome polymath chasing a number of white rabbits. Someone from our world once saved the boy crown prince of the unified Kingdom of Corea. He’s grown up trying to find her: a detective who left behind an ID lanyard.

When you visit someplace new, it’s natural to get excited about trying new things and enjoying local delicacies. Lee Gon is absolutely fascinated by the differences at any scale between his home and this odd, separate world. Yet there is something a little —mm, disrespectful about this setup. Somehow I am expected to buy that the Kingdom of Corea, a highly advanced and prosperous global power, has neither invented or imported fried chicken as a concept. In our world, Lee Gon is instantly, innocently enthralled with it. He cannot stop ordering it, looking for it and having it delivered. Thanks, BBQ Olive Chicken Café!

I love The King: Eternal Monarch. I love doppelgangers crossing parallel universes and coming face to face with themselves. I love Woo Do-hwan’s exceptional turn as the stern Unbreakable Sword Jo Yeong and his goofball lookalike Jo Eun-seop. I love Goblin heroine Kim Go-eun as a hard-bitten detective, and Kang Hong-suk as the thuggish-looking sweetpea Jang Michael, and Jung Eun-chae as the scheming high-femme prime minister. The show is very popular on Netflix worldwide — but in South Korea, it’s considered a flop.

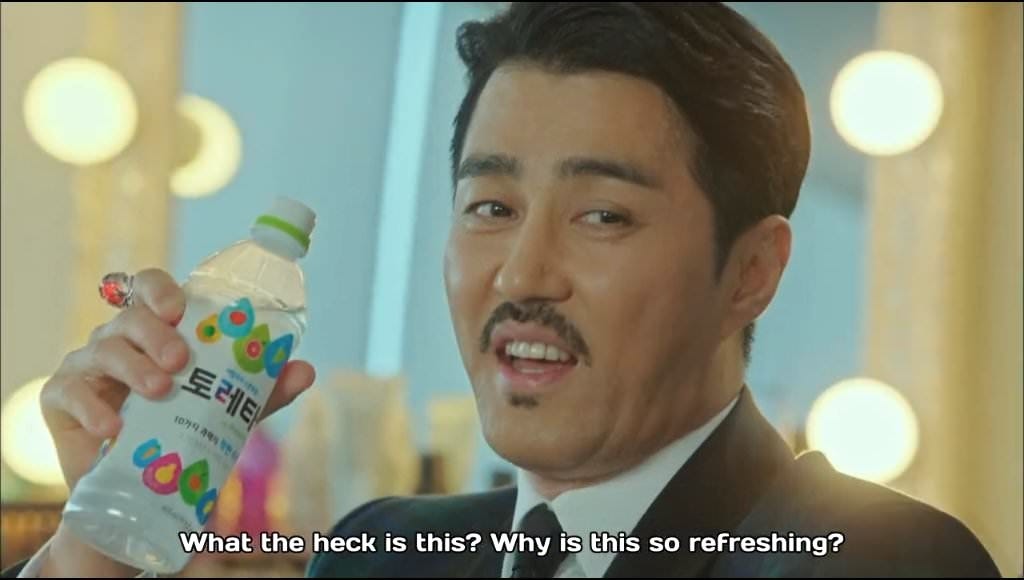

One reason may be the hilariously excessive product placement. The plot will be rolling along when all of a sudden, someone pauses to apply Kahi multi-moisturizing balm stick, recommend prepackaged kimchi, flash a particular brand of watch/sunglasses/jewelry, mix up a fancy bubble tea, park a certain expensive car, place a beverage label-out on a surface, compliment a service-economy app on a folding smartphone or don an LED skincare mask that I honestly thought was a signifier of the technologically advanced alternate universe and not a real thing that people (cough, male lead Lee Min-ho) endorse and buy.

Renting out our concentration

A surfeit of PPL, as it appears in marketing jargon, isn’t the problem of just one series. Bulgasal: Immortal Souls is a relentless and gorgeously shot work of mythic folk horror, set largely in the ruins of rural backwaters; somehow, every player drives an Audi. My beloved Goblin and Business Proposal give their leads jobs at existing fast-casual restaurant franchises and frozen food conglomerates. How many times have you watched a hero or heroine forlornly clean with a Dyson vacuum or offer a love interest an instant Nescafé product? How many bottles of soju can a drinker guzzle in one night, and how much instant ramen will help them through the hangover? Why do the most beautiful people in Seoul always resort to Subway for lunch?

We’re not letting China off the hook either. I’m especially impressed by how PPL works its way into Mainland period dramas. The xianxia BL Word of Honor, famously strapped for cash during production, relied heavily on its partnership with Wolong Nuts, which dictated characters’ snacking habits throughout the series. After the show became a phenomenon, other advertisers jumped on the bandwagon; Cadillac collaborated on a short film more or less explicitly framed as one couple’s next-life reunion. Sometimes, advertisements on costume dramas are even filmed in character and slotted “seamlessly” into the show itself:

Product placement is a way of life all over the world. In moving pictures, it was first documented in 1896, when the Lumière Brothers included branding in one of their early films for Lever Brothers’ (much later Unilever) Sunlight Soap. Even North Korean media engages in “socialist advertising,” which both promotes state-owned brands and reinforces narratives of DPRK increased standards of living, as well as the real or imagined envy of foreign nations. As the critic James B. Twitchell wrote nearly three decades ago, “Programs are the scheduled interruptions of marketing bulletins.”

Marketers, unfortunately, love product placement, especially in the age of video on demand. Audiences engage in ad avoidance at enormous rates wherever possible, skipping, blocking or disregarding traditional commercials when consuming media. However, in an unjust world such as this, sponsors are necessary to underwrite the production of our favorite filmed stories. These sponsors will get their money’s worth. Melding their products into the story itself makes them unavoidable. Twitchell again:

“These media are delivered for a price. We have to pay for them, either by spending money or by spending time. Given a choice, we prefer to spend time. We spend our time paying attention to ads, and in exchange we are given infotainment.”

Ultimately, advertisers wouldn’t rely so heavily on PPL if it didn’t work. According to BENlabs’ “The State of Product Placement in 2023,” three-quarters of U.S. consumers “have searched for a product or brand online after seeing it on TV or in a film, with 57 percent going on to make a purchase.” Complaining about product placement is loud, but money in the bank is louder.

Cause and effect and cause and effect

Product placement is baked into kdramas and c-ent, often from the ground up. The 2018 book Pop City by Dr. Youjeong Oh (available open access on JSTOR) goes deep into the business of producing and marketing both kdramas and kpop idols. Though product placement in all its diversity is regulated by the government, sponsors cover huge portions of production expenses on an average show. This is because it’s mostly independent production companies who are responsible for creating shows (and bearing the upfront costs) for terrestrial broadcast — e.g., not originally for a streaming service like Netflix, which brings its own pros and cons.

It’s a precarious way to do business, and Oh argues that it incentivizes a speculative investment environment, which brings high risk with high potential reward. This self-perpetuating system, which attracts gambling personalities, can affect the storytelling even beyond awkward asides or lingering shots of products. One production company admitted that its bodyswapping romcom “had been carefully designed from the synopsis stage to take product placement into account; the firm cooperated with a marketing firm to strategically build characters and set their occupations and residential spaces with reference to the products that were being promoted.”

Because many kdramas are filmed at a breakneck pace as they air, viewers may notice peaks and troughs of product placement. Sometimes more PPL intrudes in the back half of a show not because it’s desperate for cash, but because it’s a ratings hit and additional sponsors want to get in on the goods. Even the social media response to a show’s product placement can turn into a meme, which can generate more visibility: think posing with a drink or recreating a scene, plus obligatory hashtags.

Perhaps strangest and most fascinating, at least for Oh, is the symbiosis between filming locations and municipalities. “[F]irst, cities construct megasize drama sets to be used as major filming venues and then further developed as tourist attractions,” she writes; “second, drama producers strategically display locations from the cities featured in television dramas in return for cash support. […] Ownership of a drama set remains with the city rather than the producer. When well-managed and advertised, a set can … give a boost to the local economy.”

This long-tail effect can’t be guaranteed, of course, and it’s not unheard of for a production company to effectively dine and dash on a locale which pursued the deal in the first place because it was struggling. Too much popularity can also kill the golden goose, even far afield. The idyllic Swiss town of Iseltwald is the site of some of the most iconic scenes in the early pandemic megahit Crash Landing on You. After being swamped by tourists, not just from Korea but the world over, the village instituted a “selfie tax” on the famous pier on Lake Brienz, hoping to at least curb foot traffic and preserve some of the peace which made it famous.

Going worldwide, baby

The Hallyu Wave, the soft-power explosion of pop culture out of South Korea, emerged from the late-‘90s pan-Asian financial crisis. It is impossible to think about kpop, kdramas and other phenomena without conceiving of them as infinitely renewable exports. The 2002 series Winter Sonata was, on its release and long after, so popular in Japan that it’s credited with “causing enormous changes in cultural, economic and political arenas” in both nations, Oh writes. Meanwhile, 2003’s Jewel in the Palace famously made huge inroads with Chinese audiences (and therefore markets) — a major achievement at a time when official relations were still fragile.

The knock-on effects of the export mentality have been significant. Today, some fans complain that kdramas have “lost their innocence” in a global market that craves edgier media. Because Chinese censorship can be difficult and slow to navigate, Korean studios began pre-producing more shows, which can be approved all at once, rather than live production, which can respond as it airs to Korean audience tastes and input.

“Given that 30 to 50 percent of profits come from drama copyrights sold in the Japanese market,” Oh wrote in 2018, “the casting of idol singers has become standard practice, rather than a one-time publicity event.” It might not matter how well the idol can act — it’s the face that’s important to the fanbase, and the delivery will be dubbed abroad. It matters less that Koreans didn’t jibe with The King: Eternal Monarch; they love it overseas.

Culture, like land and spaces, can be and often is a product, displayed, transactional and managed in rhyming ways. Back in 2005, the Sinologist Yomi Braester examined “the entrepreneurial use of culture” in Chinese cinema, comparing it to the 1990s real estate boom — another speculative environment — that remade Beijing and other cities as globalization accelerated. Braester pays particular attention to a 1997 black comedy localized in English as Big Shot’s Funeral:

[A] famous Hollywood director, Donald Tyler (Donald Sutherland), arrives in Beijing to shoot an updated version of The Last Emperor and falls into a coma. The cinematographer Yoyo (Ge You) takes to heart Tyler’s request for a “comedy funeral” and plans an uplifting spectacle worthy of the director’s reputation, to take place in the Forbidden City. To cover the costs, the cinematographer takes every opportunity for direct advertising and product placement.

We can neither escape PPL nor settle on what it means, precisely. The Korean shows Sh**ting Stars,1 Be Melodramatic and The King of Dramas purport, to some extent, to show the unpleasant business-driven reality of supporting TV magic. In the U.S., legal and First Amendment scholars have wrestled with “whether the commercial purpose of [embedded] advertisements outweighs the constitutionally protected message of the program.” Nobody anywhere in the world has really found a better solution to the tension between art and commerce than to be independently wealthy.

I’ll take a note here from cranky iconoclast James Twitchell, whose 1996 jeremiad “But First, A Word From Our Sponsor” holds up in an age where selling out is all that’s left: “Ironically, we are not too materialistic. We are not materialistic enough. If we craved objects and knew what they meant, there would be no need to add meaning through advertising.”

“What is clear is that most things in and of themselves simply do not mean enough,” he concludes. “In fact, what we crave may not be objects at all but their meaning.” All of which to say is: we love the stories. We keep watching. ✶

What’s the funniest bit of product placement you’ve seen? Let me know in the comments or on Bluesky. I love recs and growing my teetering to-watch list.

Thanks for reading Excited Mark! If you’d like to support my work, please share, toss a few bucks at my Ko-Fi and/or become a subscriber, free or paid. I’m also available for hire as a fact-checker, editor and journalist — visit my RealName.com for clips, services and more.

How to Love an Actor Without Becoming Deranged

Actors and their management companies diversify their risk with product endorsements. Celebrities have social incentives for only promoting high-quality products, as significant subsets of consumers rely on celebrity credibility to differentiate between commodities. One 2019 survey found that nearly three-quarters of Chinese fans are willing to support their idols through shopping.

I don’t know if tying admiration for a celebrity so closely to consumption makes audiences objectify that celebrity more.

No, this is not a censored curse word. No, I cannot read it as “shooting” either.

The funniest PPL I’ve ever seen wasn’t even in a kdrama bit in 1993 French movie hit Les visiteurs: the posh FL suddenly stops as she runs up the main marble staircase of a chateau-turned-hotel and whips out her Visa card. Cue exaggerated close-up of the front of the card and the logo, with blurry zooming in and out effect. Not to hide the details or for artistic reasons but just because the camera can’t manage to focus! When I saw it the first time, my jaw dropped. Back then, I didn’t even know what product placement was—but I still recognized it as soon as I saw it (I guess in that it’s like pornography haha!). They couldn’t have done it more badly if they tried! I’m sure you can find it online, it’s infamous!